In the White Mountains of eastern California there is an ancient bristlecone pine forest where one of the oldest living beings on earth still grows: a Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) known as Methuselah.

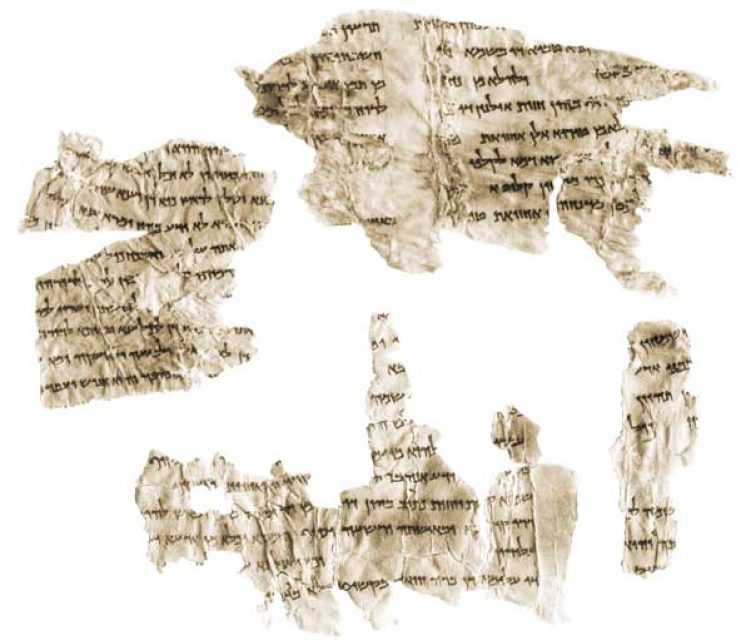

The tree is named after the oldest figure in the Old Testament, Methuselah, who according to the Bible lived for 969 years and was the grandfather of Noah. Although disputed, the traditional view holds that Moses wrote Genesis around 1400 BCE, following the Exodus from Egypt. By then the Methuselah tree had already been alive for nearly a millennium and a half. Curiously, the being that bears the patriarch’s name predates the very text in which he appears.

In 1957 scientists sampled and dated the tree, estimating its germination around 2830 BCE, close to 5,000 years ago, a time when the pyramids of Egypt were being built and Sumerians were inscribing the first cuneiform tablets.

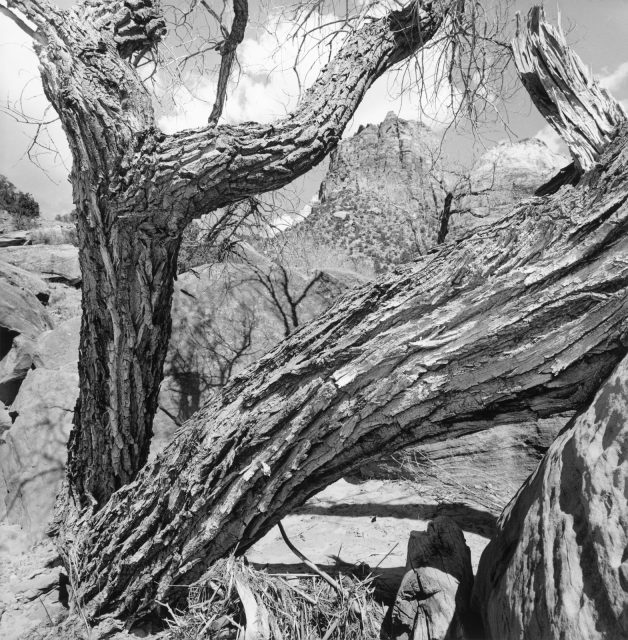

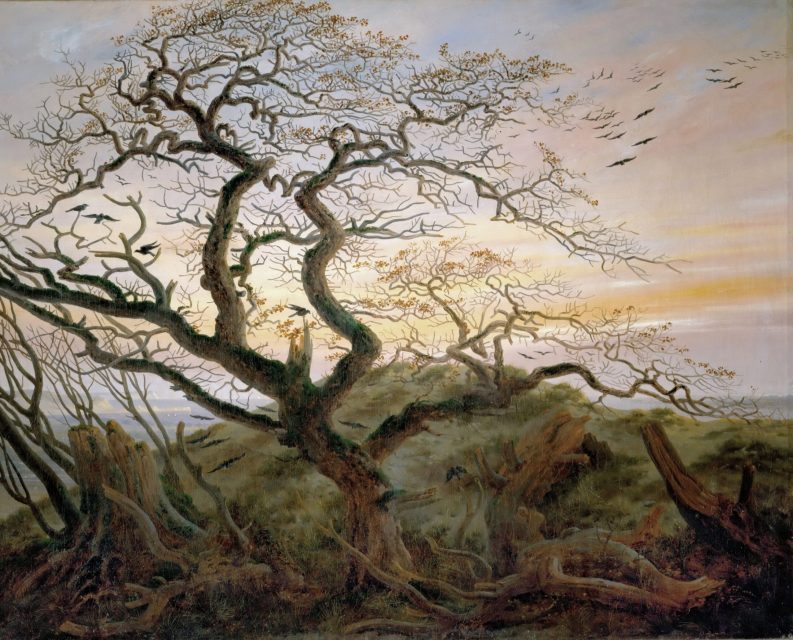

Bristlecone pines are known for their extreme longevity, with many individuals surpassing 4,000 years. Their endurance is not the result of favorable conditions but of the harshness of the high-altitude alpine desert: thin rocky soils, intense sunlight, strong winds, and extreme cold. Growth is painfully slow, yet disease and competition are minimal. Rather than dying all at once, bristlecones often live in a state of partial survival. One section of trunk may be bleached and lifeless while another narrow strip of bark continues to carry sap, allowing the tree to persist for millennia. Their twisted, sculptural forms embody bare survival, shaped by adversity.

The White Mountains are geologically stable. Erosion is slow, vegetation sparse, and there are no major disturbances like floods or fires at that elevation. As a result, Methuselah has likely stood in a landscape remarkably similar for thousands of years: windswept ridges, thin air, cold nights. For most of that time, it has lived unwitnessed, outside human narrative.

The U.S. Forest Service long kept its exact location secret to protect it from vandalism. In recent years, however, photographs in popular media such as National Geographic revealed enough detail that the specific tree has been identified by the public.

Perhaps our fascination with Methuselah reveals less about ancient trees than about our own relationship with time. We project our hopes and fears about time and death onto its endurance. Its life may be less a story of flourishing than a slow continuation, closer to duration than to vitality.

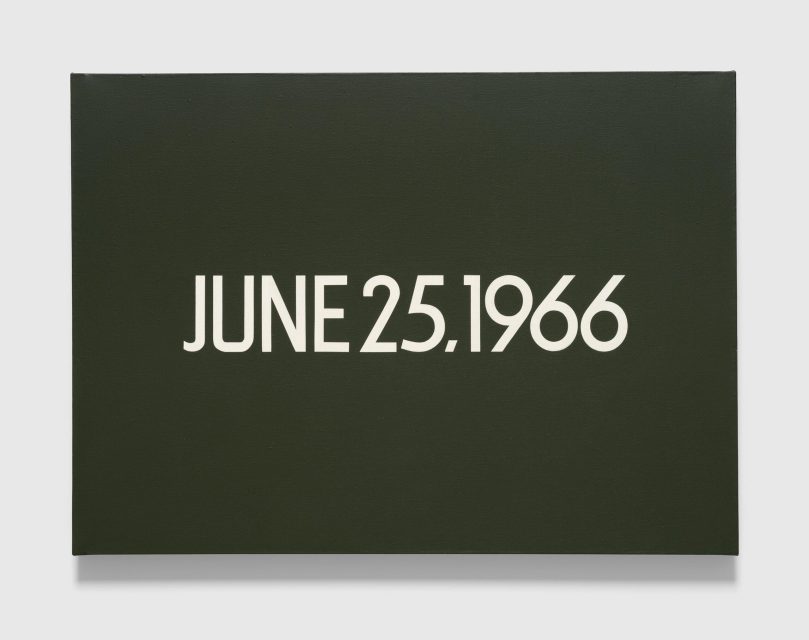

In his poem For the Anniversary of My Death, W. S. Merwin gives voice to something deeply human: not only the knowledge of an ending but the way that knowledge shapes our astonishment at being alive at all.

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what