For sexual desire, twoness is essential. The feeling of incompleteness is not a flaw but a condition. It is what draws one body toward another and keeps desire in motion. Most forms of intimacy accept this tension and learn to live with it. They circle in and out of distance rather than trying to abolish it.

Moments of being madly in love can give rise to a more extreme impulse. A desire not merely for closeness, but for the elimination of distance altogether. This wish is not primarily erotic. It is a deeply rooted longing for fusion.

During his 2007 television interview, Armin Meiwes, who in 2001 consensually killed and ate another man, explains his cannibalistic fantasy as rooted in experiences of abandonment during childhood. He refers specifically to being left by his father and his older brother.

In response to this absence, he began to fantasize about having a younger brother, loosely modeled on the character Sandy from the 1960s television series Flipper. Over time, this imagined relationship underwent a decisive shift. The fantasy no longer centered on companionship alone, but on incorporation. The imagined brother was no longer only someone to be kept close, but someone who could be consumed, so as to integrate the other person into oneself.

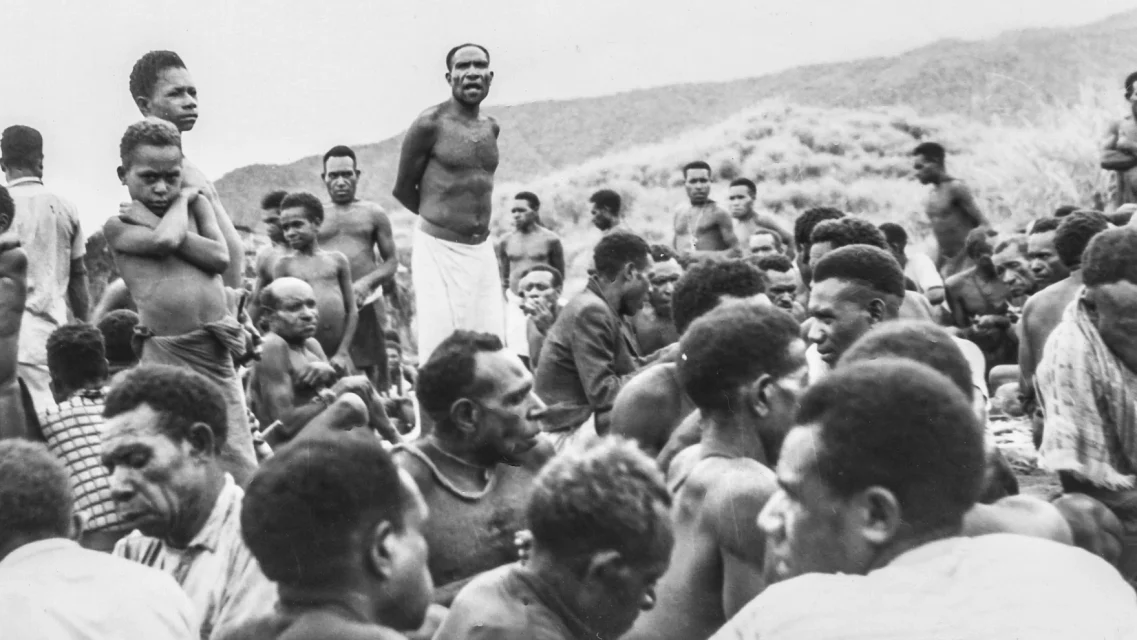

This idea is far from singular. It appears in much older contexts as well. In communities practicing institutionalized endocannibalism, the consumption of the corpse is not understood as an act of aggression, but as an expression of affection. Eating the dead allows the deceased to remain present in a physical sense, not merely as memory or symbol, but incorporated as part of a living human organism.

Meiwes himself points to a cinematic image as a key moment in the formation of this fantasy. He describes a film adaptation of Robinson Crusoe, in which two tribesmen wash ashore on a deserted island, one of them already dead. In the film, the surviving man expresses the wish to eat the corpse, not out of hunger or hostility, but in order to honor the dead and to keep him present. Cannibalism appears here as an act of devotion, a means of preventing disappearance.

Since the dawn of Christianity, the accusation of cannibalism has accompanied it as well. Its central ritual, the Eucharist, is based on the ingestion of the body and blood of Christ. Through this theophagistic act, fusion is ritualized. The community is unified, and the divine body is incorporated into the bodies of the faithful.

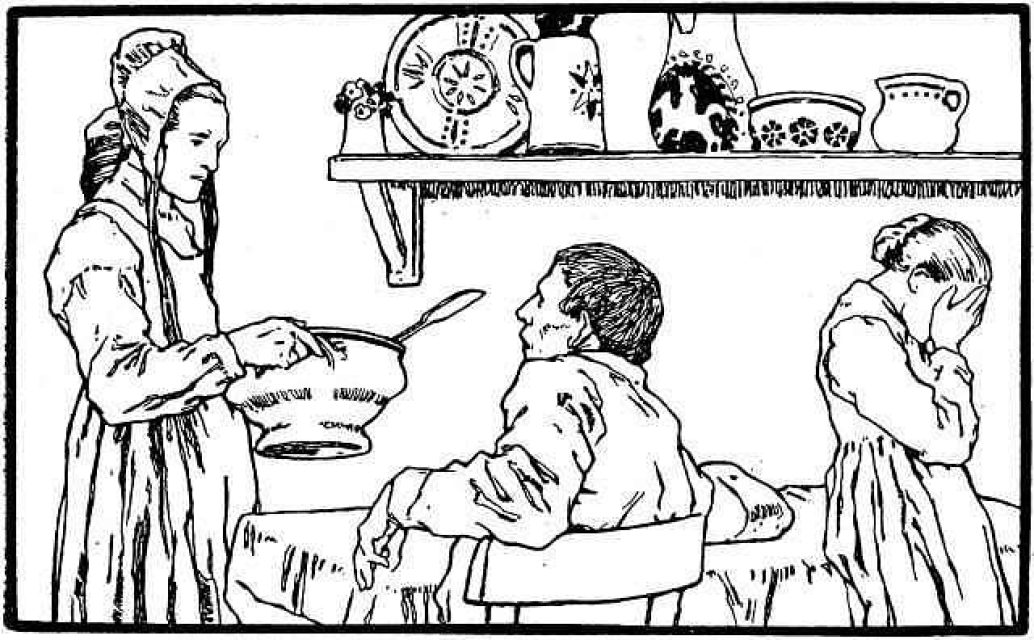

In fairy tales such as The Juniper Tree and Hansel and Gretel, cannibalism occupies a central and domestic position. In The Juniper Tree in particular, transformation becomes possible through the unknowing consumption of the dead child by its father. Absorption does not erase the child, but becomes the condition for his return in altered form.

In a twisted way, a utopian idea underlies the consumption of another human being. The digestion of a dead body promises the conversion of flesh into renewed cells, allowing the dead to persist within the living organism. Cannibalism can thus be understood as an attempt to defeat finality through consumption.