Shortly after moving out of my parents’ home, I was living in my first small student flat in Düsseldorf. One night in summer, I left the light on before going out, with all the windows open wide. When I came back home, the ceiling was covered with insects, some sitting still, others circling the lamp. It took me until the early hours of dawn to chase them with a piece of cardboard and push them back out through the windows.

The behavior of moths in relation to light has long served as a metaphor. In English, the proverb like a moth to a flame is usually used to describe a fatal attraction. In German, wie die Motten zum Licht uses the same image but carries a different emphasis, describing a predictable collective movement, often with a faintly dismissive undertone.

The behavior of moths circling a streetlight or spiraling into a fire is easily observed. From a human point of view, this visibility combined with the apparent absurdity of the action makes the metaphor almost unavoidable.

Early assumptions were that moths were attracted either by the heat of a light source or by light itself, an attraction that was often read as resulting in a kind of unintentional, self-destructive behavior. These explanations proved insufficient, however, since cold light sources such as LEDs or fluorescent lamps attract moths nonetheless. Moreover, a simple phototactic movement toward light does not account for the circling and spiraling flight patterns the insects exhibit around a light source.

A more recent line of thought introduced celestial navigation as a possible explanation, suggesting that moths use the moon and stars as orientation aids. However, moths do not actively fly toward the moon in natural conditions. Another frequently proposed theory suggests that insects move toward light as part of an escape response, since in a dark environment, such as a cave, a bright opening would usually indicate an exit, though this does not account for the circling and persistence observed around artificial lights.

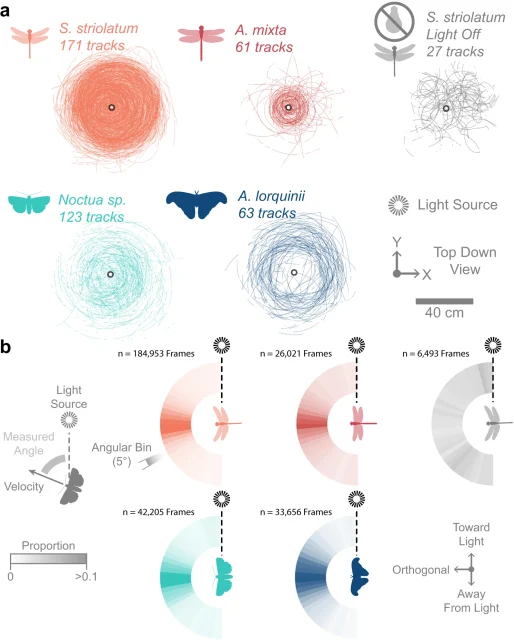

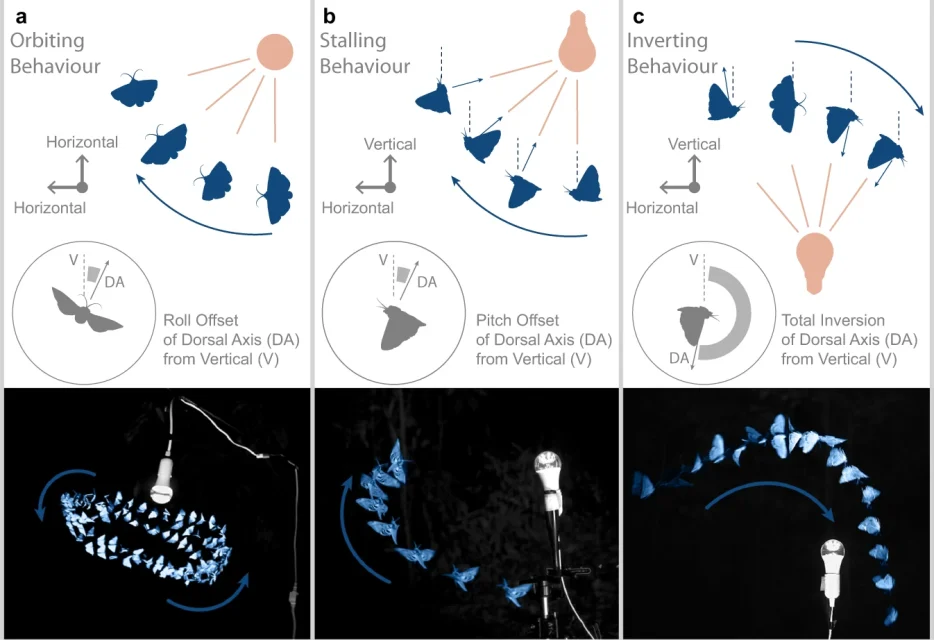

Using contemporary techniques such as high-resolution motion capture and stereo videography, biologists were able to show that the entrapping effect of artificial light is linked to a shift in the insect’s sense of vertical orientation. Apparently, the animals maintain their dorsum oriented toward the light, which results in a perpendicular looping movement around the light source.

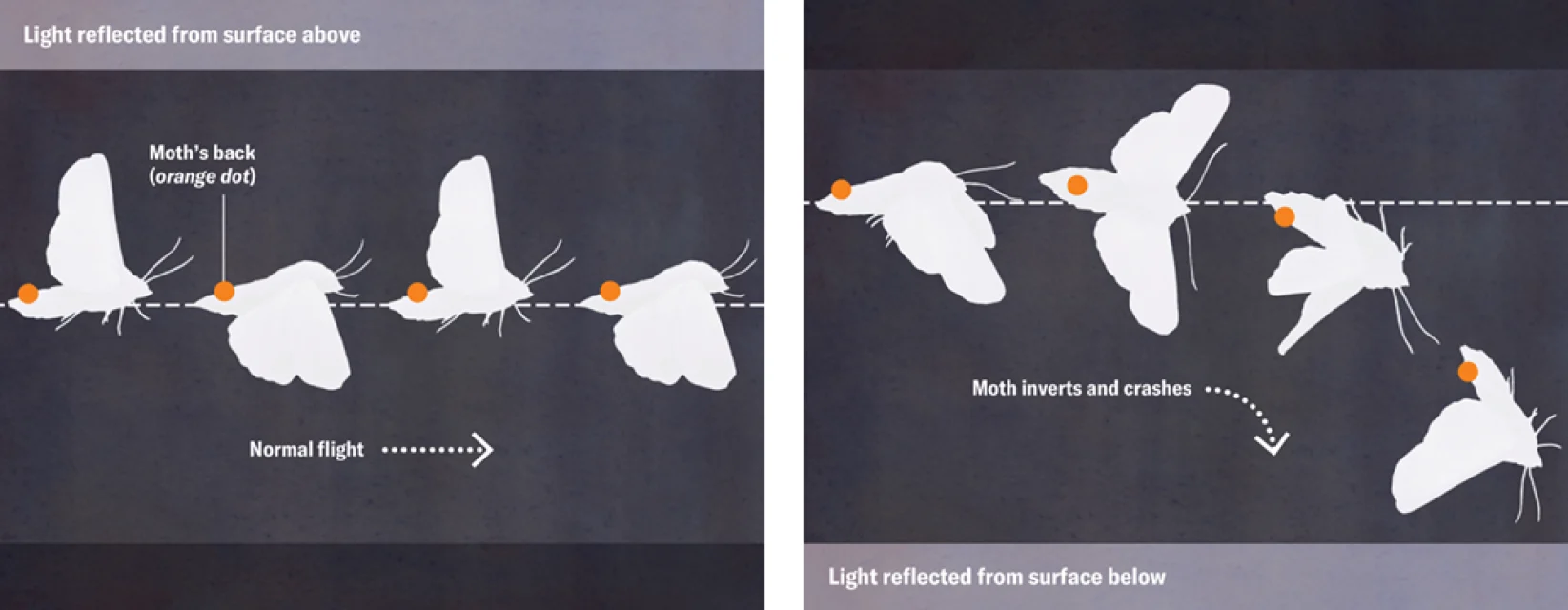

What the light seems to do is disrupt the insects’ sense of up and down, triggering a constant need for adjustment. Normally, up corresponds to the sky, which remains lighter than the ground, even at night.

Light does not, in itself, seem to attract moths. In one experiment, among fifty moths released eighty-five meters from a strong artificial light source, only two ended their flight at the light. Instead, artificial light tends to entrap insects once they pass into its immediate vicinity, disrupting their ability to maintain forward flight and holding them in a repetitive motion around the source. This behavior is often only interrupted by chance events, such as a gust of wind, that carry the insect out of the light’s direct influence.

Certain lamp orientations appear to be particularly disruptive in this regard. A downward-facing light, when reflected from the ground, can trigger a tailspin in approaching insects, causing them to flip onto their backs and crash. A single light source positioned above the insect, on the other hand, tends to induce upward flight followed by stalling.

There are still unresolved questions concerning this behavior. It remains unclear why some insects settle on or near light sources, or why natural celestial light or reflections do not produce the same kind of erratic response.

![Philipp Fröhlich's painting Fläche und Durchmesser [Surface and Diameter] (285L), 2020, oil on canvas, 110 x 145 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Philipp_Frohlich_Flache_und_Durchmesser_I_2020_145x110cm_285L.jpg)

![Philipp_Frohlich_Fläche_und_Durchmesser_I_2020_145x110cm_(285L) Philipp Fröhlich's painting Fläche und Durchmesser [Surface and Diameter] (285L), 2020, oil on canvas, 110 x 145 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Philipp_Frohlich_Flache_und_Durchmesser_I_2020_145x110cm_285L-rio8m3g2xwxdkqibfakzofpvcrn7diyta2hy5q5pts.jpg)