One of the most satisfying things I have done in recent years was to install a bird feeder in the middle of our small garden. I watch the birds from our kitchen window every day. It is mostly titmice, sometimes finches and robins. Now and then pigeons or magpies squeeze into the tight frame of the feeder.

It is striking how easily we accept birds in our immediate surroundings. They live beside us and we barely register one another. The same level of coexistence would be unthinkable with mice, rats or insects that also share our urban space, only far less welcome.

Crows, gulls and magpies are constant companions in Brussels. They are commensals, benefiting from our presence. Often, they tear open garbage bags, yet the sight never provokes the disgust that rats would cause.

Birds have no odour and pose little direct threat. They neither bite nor sting, and their space is the air, a place to which we have only limited access. Air and trees seem cleaner to us than soil and the low ground where insects and rodents live. Birds remain close without competing for our space, and their presence offers a small glimpse of nature within urban surroundings.

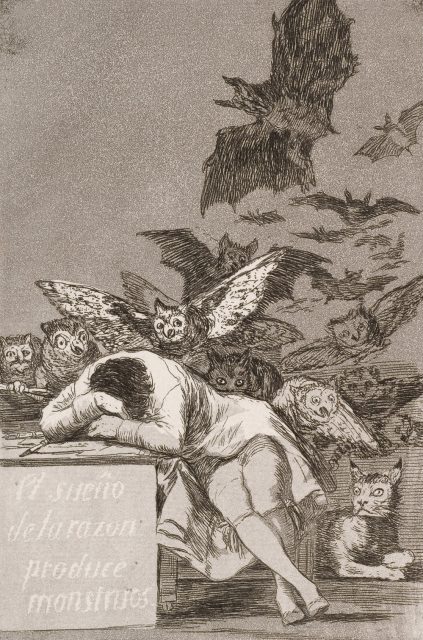

There is a long cultural hierarchy linked to altitude. Heaven above and hell below. Gods in high places, demons under the earth. Our language repeats this structure with words like uplifting or noble opposed to lowly or base. Even the human body follows this axis with the head raised and excrement close to the ground.

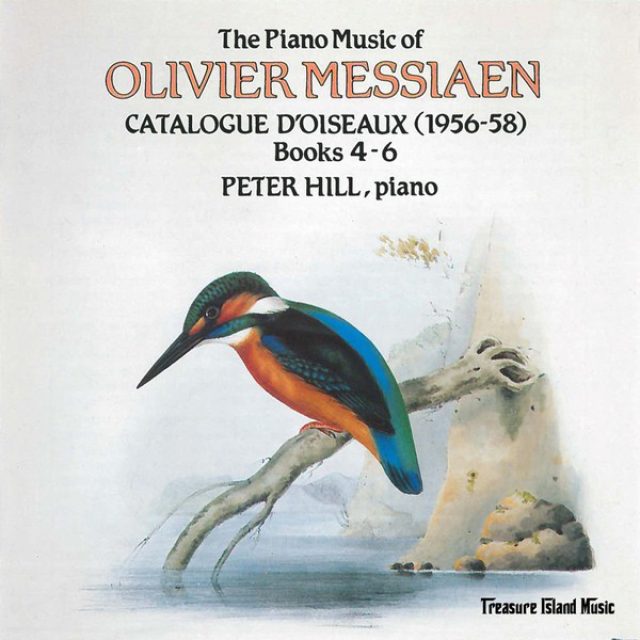

Birds occupy this privileged vertical zone which creates admiration and maybe a little envy. We forgive their noise and droppings far more readily than we would tolerate similar intrusions from other animals. Although some species croak or rasp, we rarely treat their sound as a disturbance. Birdsong and flight are usually received as aesthetic rather than alarming.

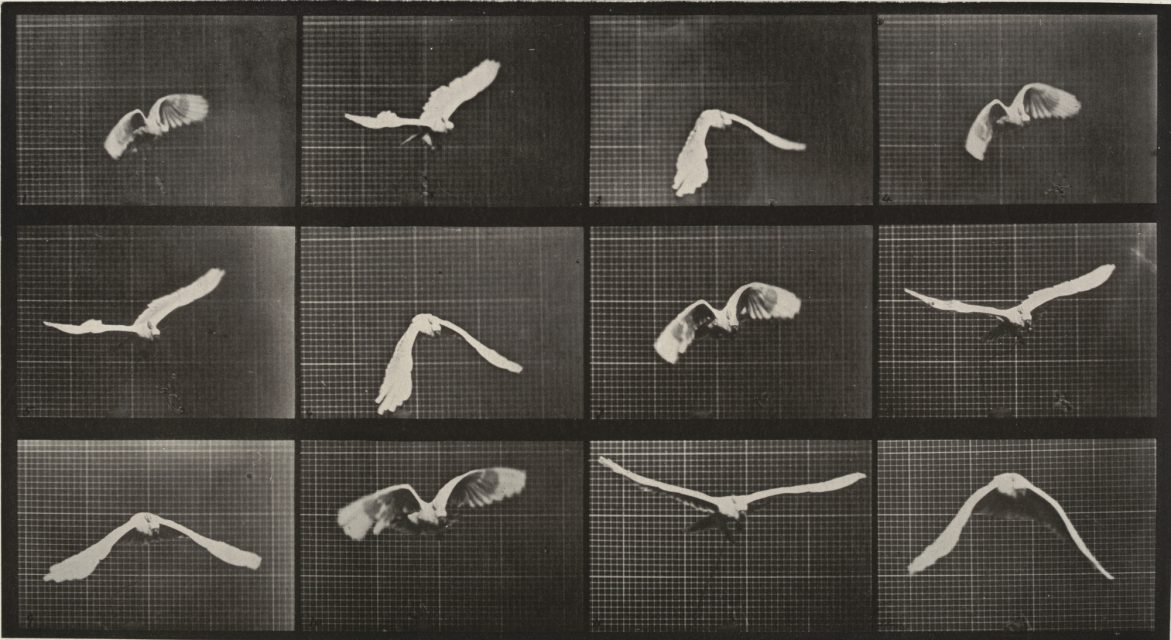

Many insects fly as well, yet apart from butterflies we rarely feel much empathy for them. Birds move in arcs and glides that our eyes can follow. Insects seem to dart and circle without pattern. We can read rhythm and intention in a bird’s movement, but not in a fly’s. Birds announce themselves through their song. Insects appear abruptly, buzzing and at close range. They are linked to decomposition and invisible labour.

Across cultures we have invested birds with symbolic meaning. Insects are rarely granted that status. When insects do appear in stories or images, the result is often estrangement or discomfort, as in Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Birds, by contrast, find an easy place in our everyday life and do not cause the same sense of disturbance.

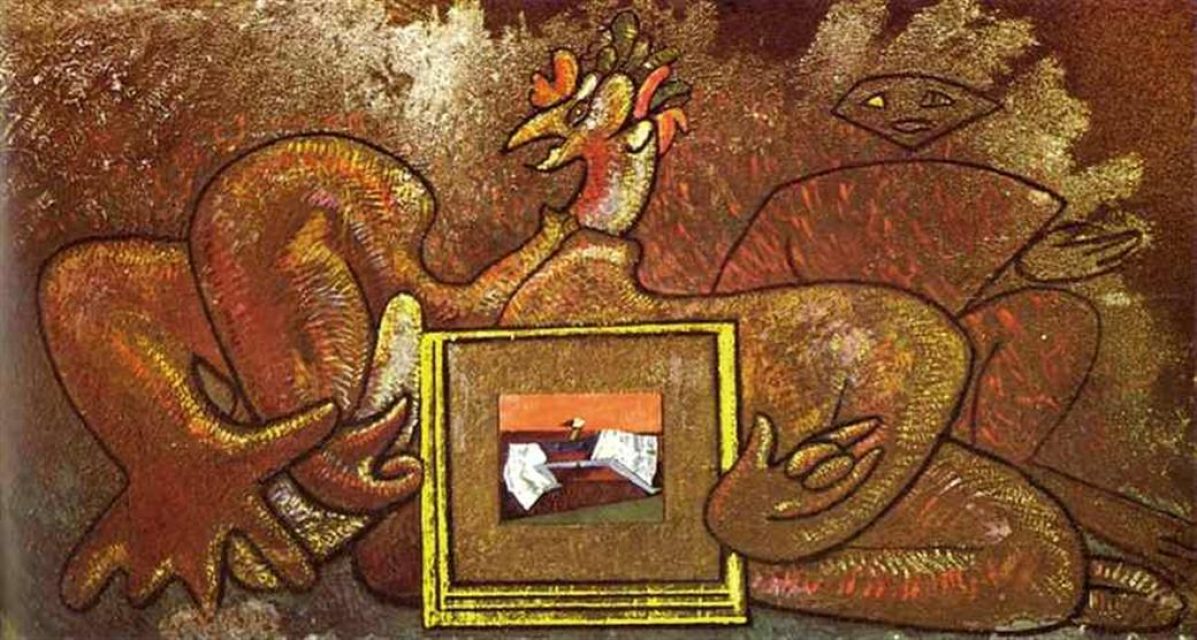

La Cavale means the escape in English. Birds do this constantly. It is a painting about a brief shift in attention and a small reversal of hierarchy.