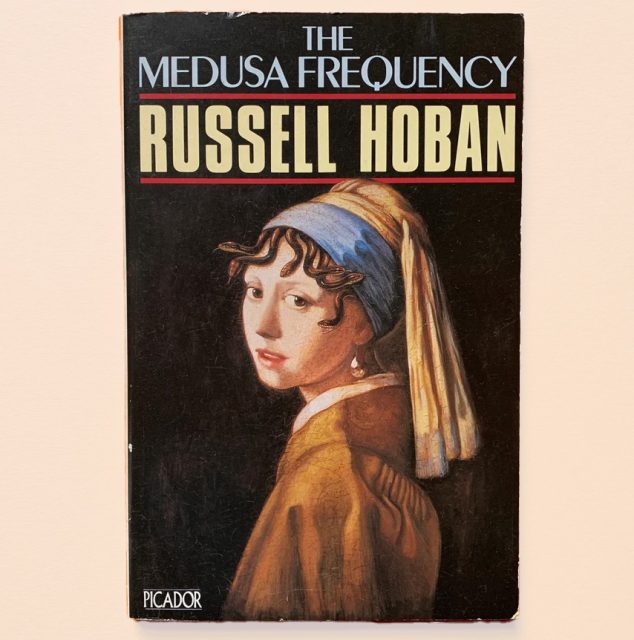

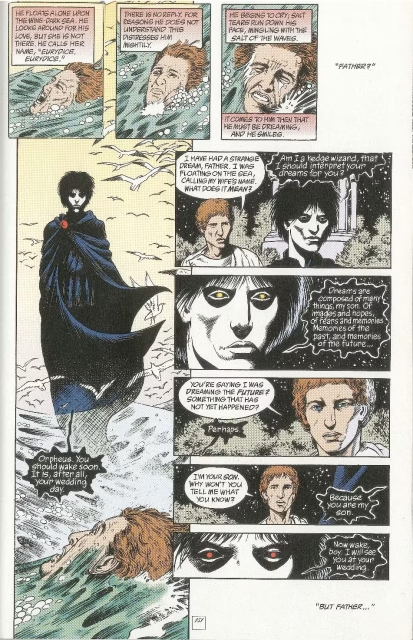

Upon encountering a cabbage floating in the River Thames, the main character in Russell Hoban’s The Medusa Frequency hallucinates: the cabbage becomes the severed head of Orpheus, drifting in the current, murmuring stories. An image that borders on the absurd, almost comical.

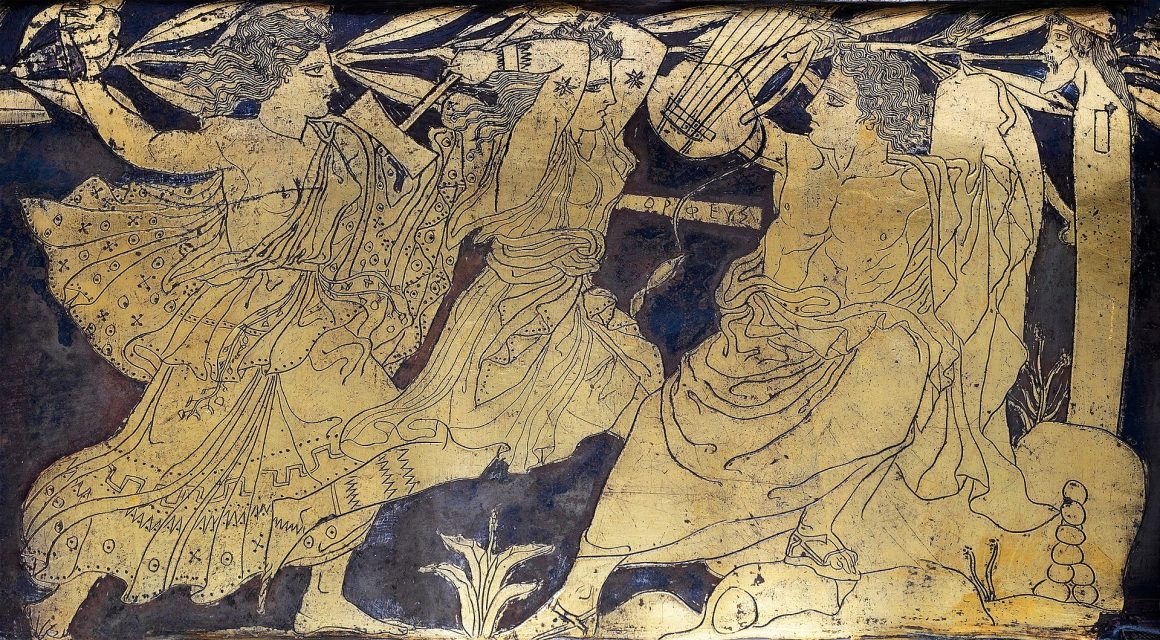

According to myth, after the Maenads, raving female followers of Dionysos, tear Orpheus apart in a ritual frenzy, his head and lyre float down the River Hebros, still singing, still playing. Apollonian order and harmony are undone by ecstatic chaos.

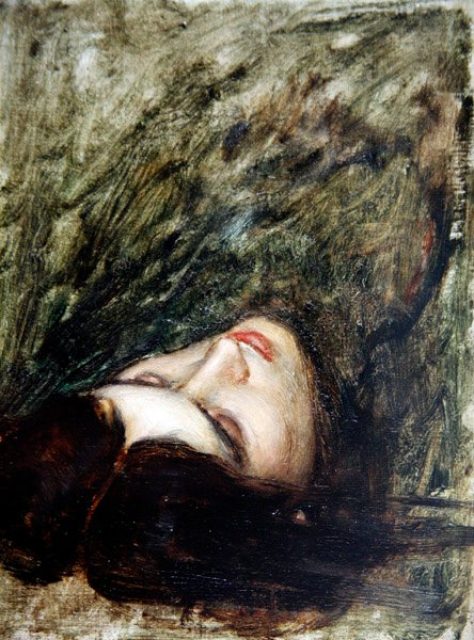

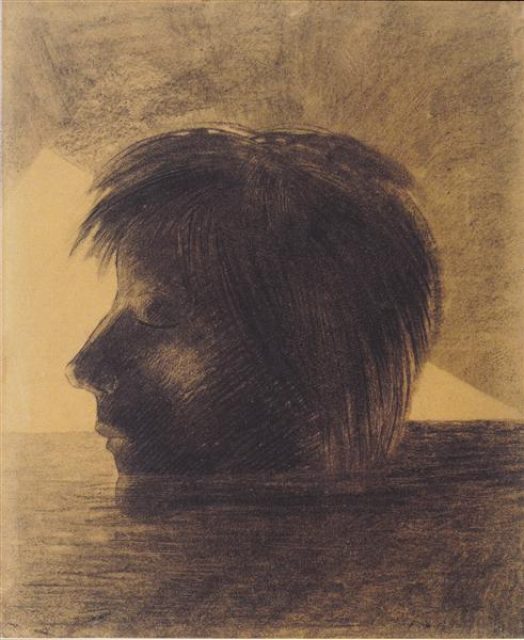

The dismembered, floating head of Orpheus became a favored subject among Symbolist and Pre-Raphaelite painters of the 19th century, always suspended between pathos and detachment. There is survival in this image, but it is survival as estrangement: the head without the body, still sounding, but adrift, without the will to seek an audience. It is displaced in an unsettling way.

It reminds me of Goya’s El Perro (The Dog), from the Black Paintings, showing only the dog’s head, nostrils just above an undefined mass into which he seems to be sinking. Like Orpheus’s head, it is cut off from its body, its environment unclear, suspended in the empty verticality of the painting.

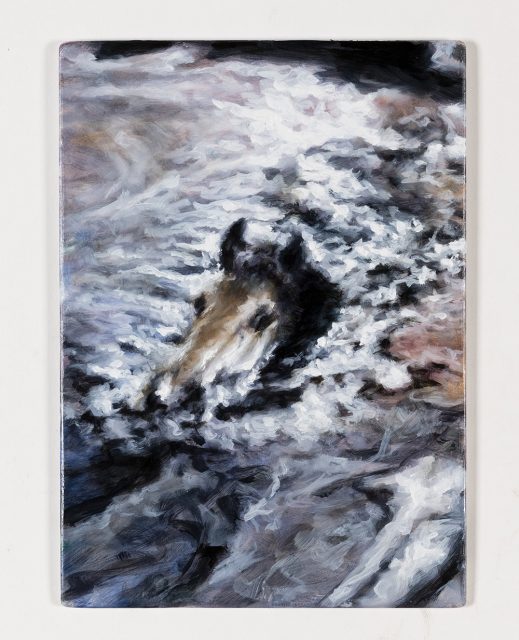

In Greek mythology, Poseidon, the god of water, also created the horse. Perhaps there is an association to be made between a galloping horse, its mane flying, and the movement of water in waves. In a way, the seahorse, with its horse-like head and curled fishtail, reflects another possible connection.

Still, although naturally capable of swimming, a horse appears completely alien in the water. Its body is essentially made for running. The long, tapered legs struggle to keep the nostrils above the surface, to fill the large lungs with air, which, in turn, keep the heavy body afloat.

There is a poem by Boris Slutsky titled Horses in the Ocean, about a sinking ship and the thousand horses it carried as cargo, now forced to swim. Here is a translated excerpt:

As for the horses, their plight was grim,

For, like it or not, they had to swim.

On and on they swam after the boats,

An island of horses with red-brown coats.

At first, they were calm, for they did not dream

That the ocean was anything but a stream.

But it stretched without end like a wintry night,

And the longed-for land was never in sight.

On their watery way all their strength was spent,

And they whinnied in fear and in wonderment.

They whinnied and neighed and struggled for breath,

As down they went to their watery death.

I can imagine the surface of the water as a horizontal cut. Not violent, but a cut formed by its own visual logic. What remains above — the head — is shown. Below is only speculation.