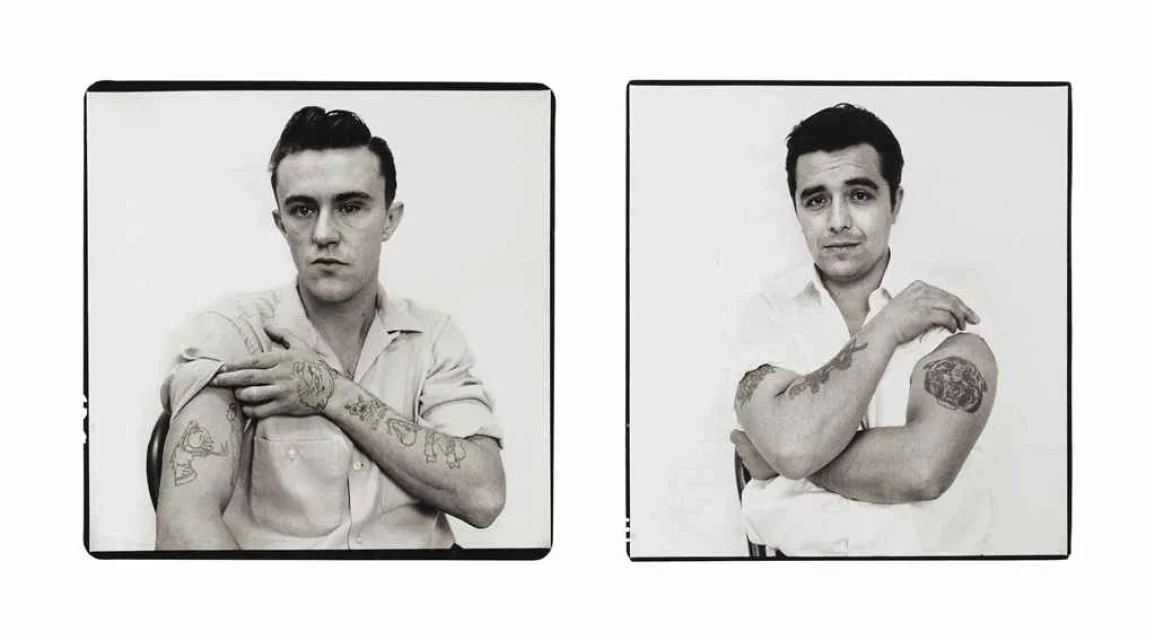

I had been obsessing over crime scene descriptions and photographs for more than a year and had finished twelve small-scale works based on serial killings when I came across an old Time Magazine article titled KANSAS: The Killers.

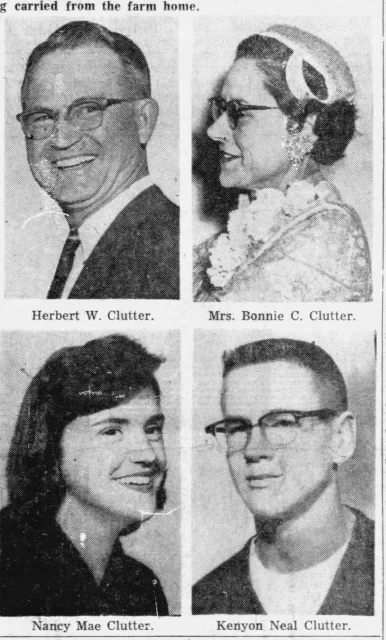

It was this same article that first caught Truman Capote’s attention and led him to write In Cold Blood. After opening with a quote from Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel and a brief introduction to the victims and killers, the piece recounts the murders in the barest outline:

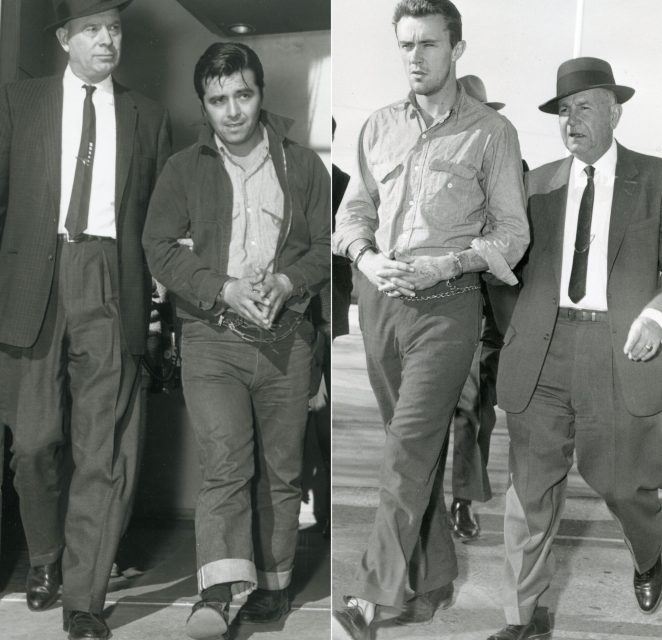

“…In November, they confessed, they drove to the Clutter farm in the middle of the night, entered the house through an unlocked door, herded the Clutters into a bathroom at shotgun point. Hickock stood guard over them while Smith futilely searched for the imaginary safe.

After giving up hope of a big haul, the thugs bound and gagged the Clutters, then cold-bloodedly slaughtered them one by one, shooting each in the head with a shotgun held a few inches away. Then, after carefully collecting the fired shells, the killers hurried away with their skimpy loot: a portable radio, a pair of field glasses, about $40 in cash. Why did they murder the Clutters? Explained Hickock: ‘We didn’t want any witnesses.’”

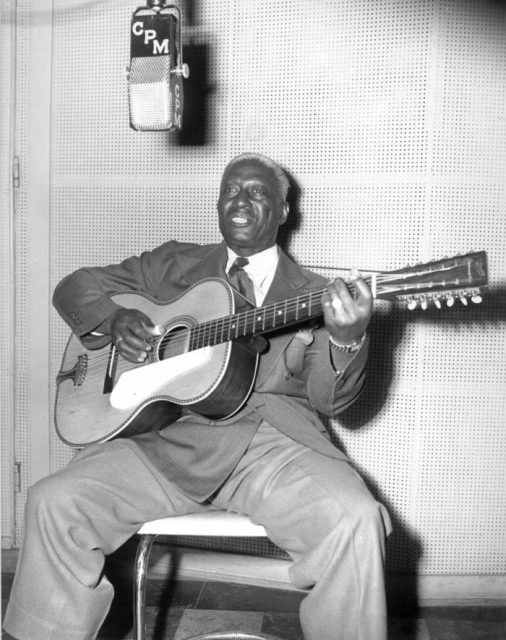

The facts are there, but nothing more. The stark brevity and directness reminded me of old blues songs, like Lead Belly’s In the Pines, where a fragment of violence appears without warning, stitched into the lyrics with the same rudimentary force:

My husband was a railroad man

Killed a mile and a half from here

His head was found in a driver’s wheel

And his body hasn’t ever been found

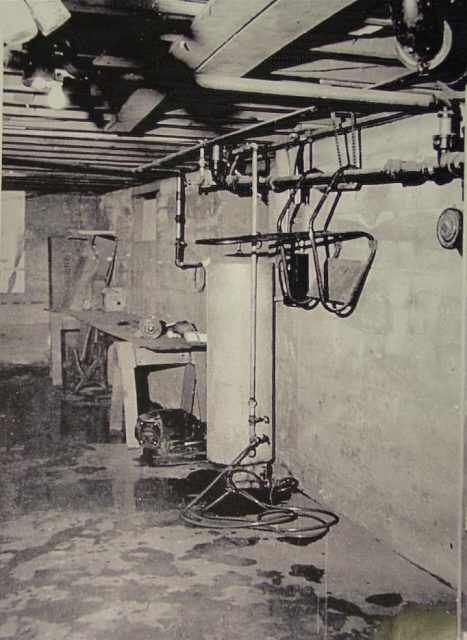

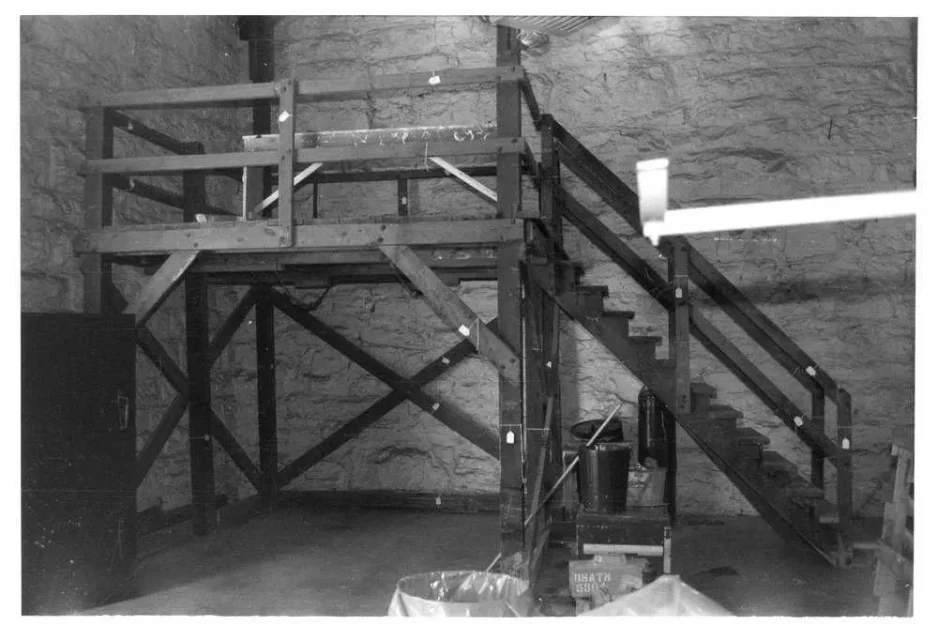

There are photographs from the Clutter crime scene that are equally fragmentary. At the time of painting, I had only a handful, all in poor resolution. The one that held me most was of the furnace room in the basement. Judging from Capote’s book, this was where Herb Clutter and his son Kenyon were tied to an overhead pipe and where Herb’s throat was cut before he was shot.

Yet the image itself shows no violence at all. It is flat and frontal, almost geometrical: a wall, beams, pipes, a furnace, a table, and a reflection on the floor. Its accidental formalism reminded me of a Mondrian painting drained of color. From my blurred copy it was hard to tell anything apart. I mistook beams for pipes, and in the background a vague shape looked like a board or painting. I now know it was bunches of weeds, tied together and pinned against a white surface.

Crime scene photographs often spark my imagination. They are involuntary stages for horror or tragedy, yet they retain the banality of a place chosen almost by accident. Perhaps it is this banality that unsettles us. The images tell us that something happened, but not what it was or how it unfolded.

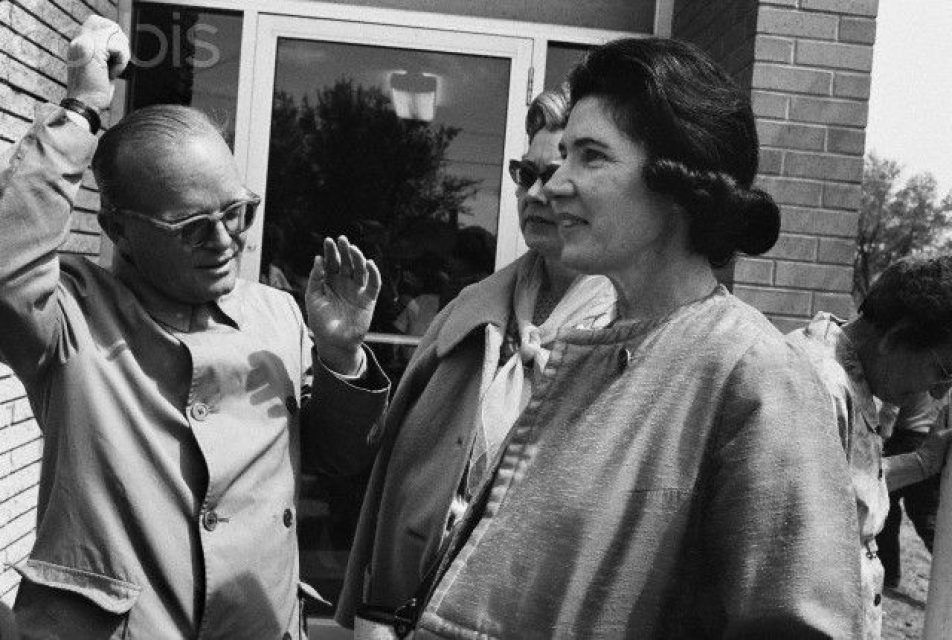

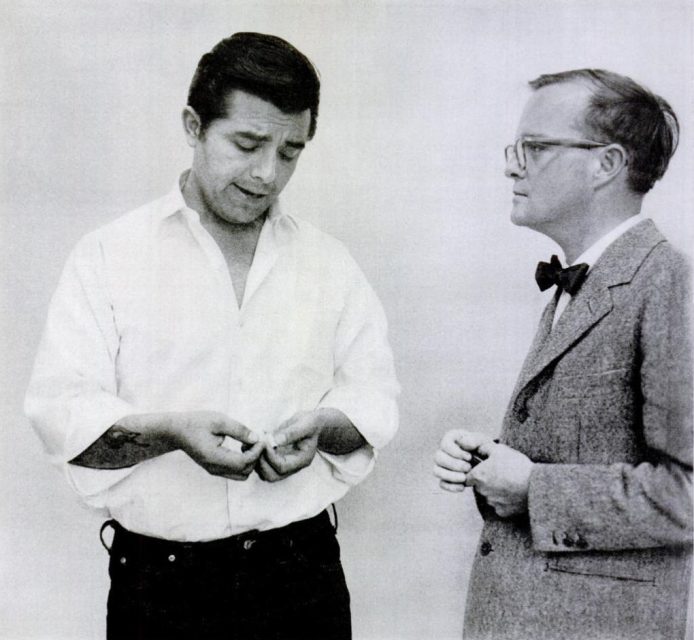

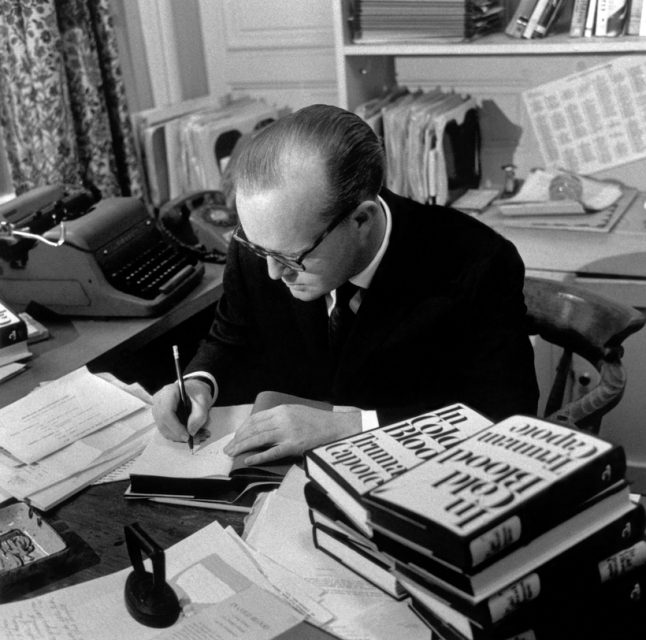

It was precisely these gaps that drew Truman Capote to the story. He travelled to Holcomb after reading the article, accompanied by his friend Harper Lee. He attended the trials, interviewed the killers again and again, and spent years researching the case. He even waited until the executions before publishing his book, believing the story needed a final act. Capote insisted on the absolute factual basis of his work. He called it a “nonfiction novel” and described it as a journalistic experiment, committed to filling every gap with verifiable truth.

While I deeply admire In Cold Blood for its character studies, social background, psychological insight, and narrative density, I find that sometimes the fragmentary openness of a note or a photograph is what most sets off the imagination. The theater of the mind does the rest.