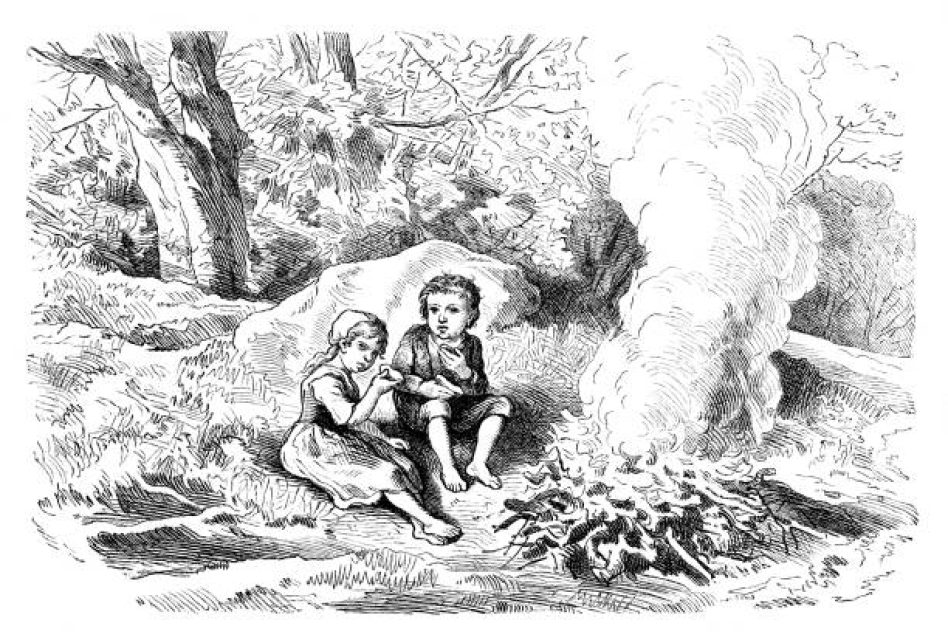

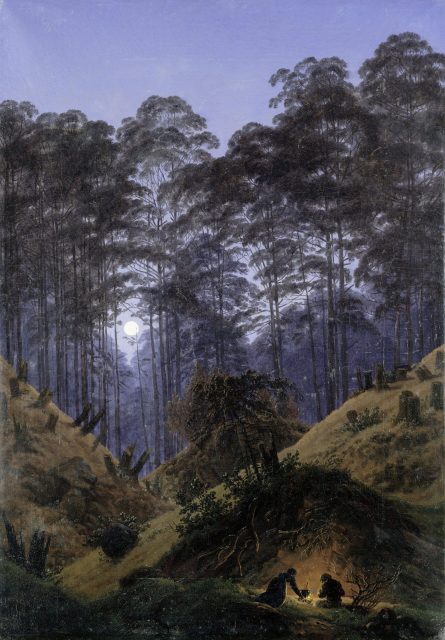

“Now lie down by the fire and rest yourselves, you children, and we will go and cut wood; and when we are ready we will come and fetch you.” This is what the mother says to Hänsel and Gretel in the famous tale of the Brothers Grimm. Lighting the fire is the last piece of domestic care the parents provide before leaving their children to their fate.

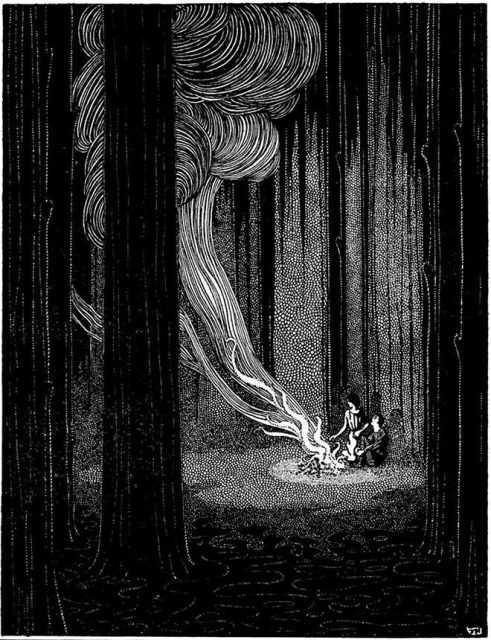

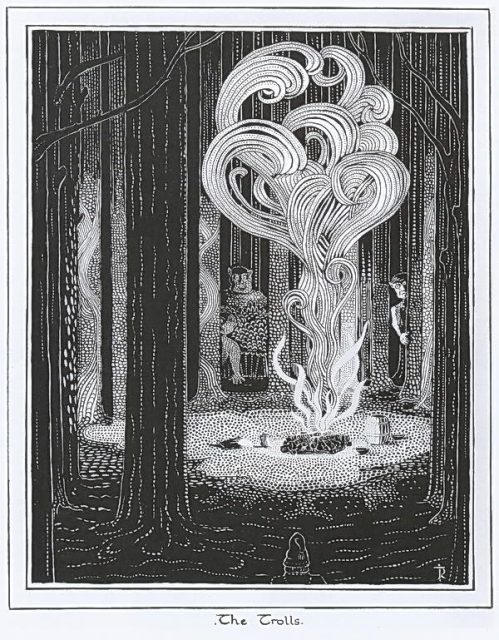

In Hänsel and Gretel, the forest is a labyrinthine wilderness, the archetypal unknown. It offers neither shelter nor comfort, and food is reduced to scattered berries. For the children, survival on their own is impossible. The bonfire stands as an island of hope and civilization within this wilderness, a fragile promise of return. Its light marks the last threshold before the unknown that lurks beyond. In reality, though, it is a prop in the parents’ performance, a semblance of care that conceals betrayal.

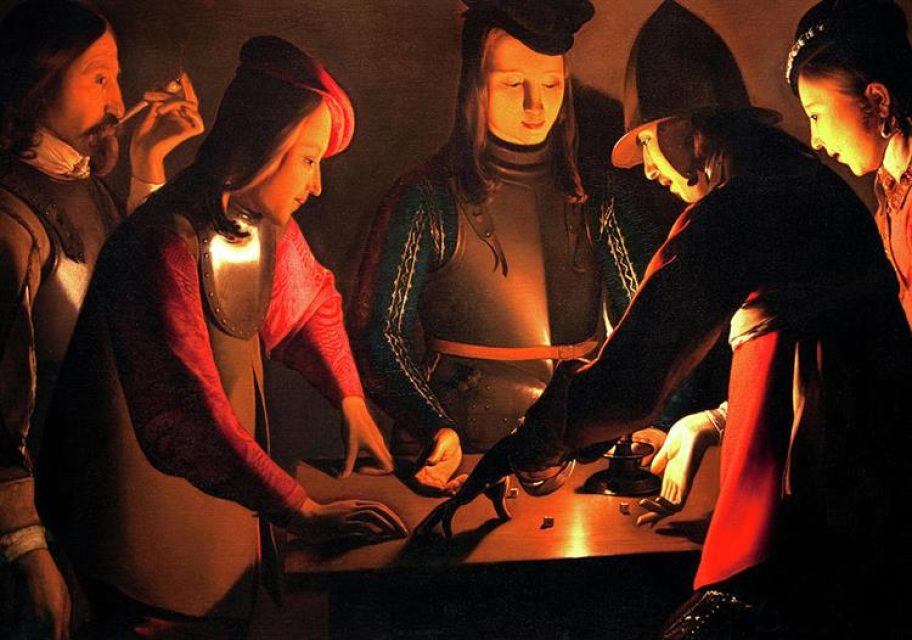

To make the children believe their parents are close by cutting wood, the father ties a branch so it knocks against a tree in the wind, a primitive sound effect sustaining the illusion of protection. Although the children have overheard their parents’ plot, they continue to cling to hope. They could head back to the family home before sunset, guided by the stones or breadcrumbs Hänsel dropped along the way. Instead, transfixed by the promise of return, they remain by the fire. Hope, bent beyond all reason, becomes a trap.

The fire itself becomes a timepiece. As it consumes its fuel, it counts down like an hourglass, measuring how long the illusion can endure before collapsing into truth. Then the children must accept that no one is coming back.