During my rebellious teenage years, I went through an extended phase of wearing only black, with my hair dyed to match. Thankfully, it passed with puberty and gave way to a more nuanced relationship with colour. One thing did stay with me, though: a lingering caution around anyone who insists on dressing exclusively in black.

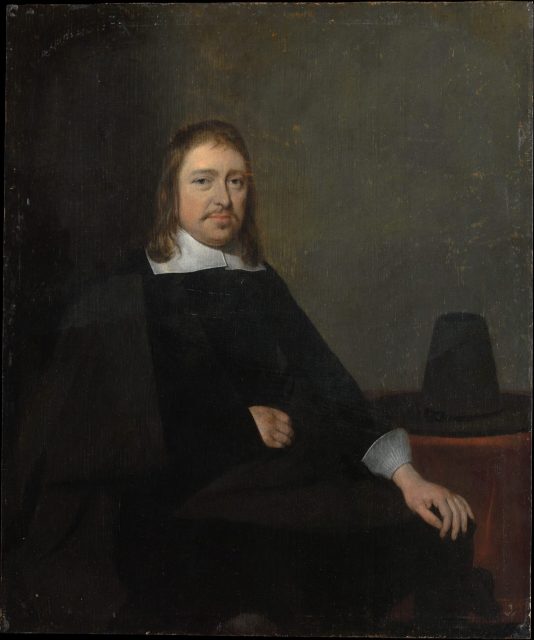

No colour carries the same charge in self-presentation. Black has long oscillated between extremes: authority and dissent, humility and elegance, mourning and emotional distance. Monks wore it to renounce the world. The Spanish court turned it into a statement of power, dyeing structured silks and velvets in deep, saturated black, made possible by advancements in technology and access to the Americas. The Dutch, under Calvinist restraint, wore black more modestly, but with no less deliberation. In all cases, black was both message and material.

In the twentieth century, the stark presence of black was claimed by all kinds of groups. The SS used black uniforms to suggest elite status and command fear. Anarchists used black to reject flags and nations. The Black Bloc turned it into tactical anonymity. The Black Panthers used it to declare pride, militancy, and visible resistance. Many artists and intellectuals still wear black, perhaps believing that gravity of thought is best reflected in the absence of colour.

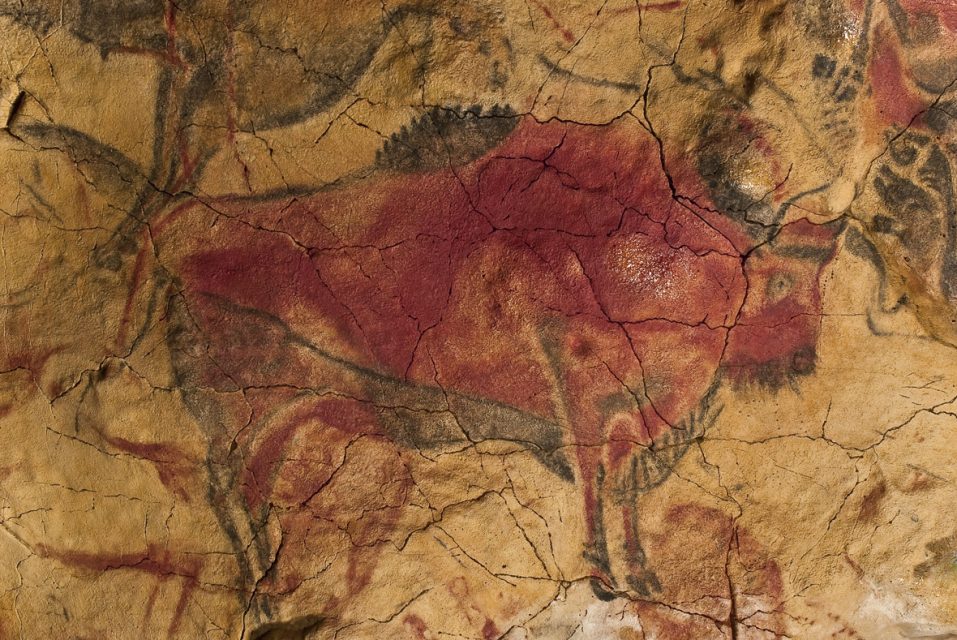

In painting, black was one of the earliest and most accessible pigments, usually in the form of charcoal or soot. Astonishingly, these materials remain in use today as lamp black and bone black.

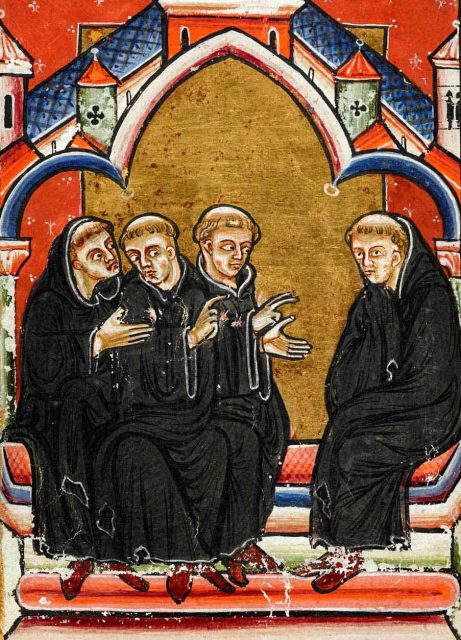

From prehistoric caves to medieval manuscripts, black pigment was used primarily to frame figures, define edges, and sharpen contrast. During the Renaissance, pure black was rarely used on its own. Painters preferred layering madder lake with indigo, or umber with azurite, finding these mixtures warmer and more alive than black alone, which was considered flat and lifeless.

The Baroque period changed this. Improved pigments like ivory black, combined with theatrical compositions that used darkness to shape space and heighten drama, made black a central force, charged with gravity, moral weight, and tension.

In the 19th century, black took on divergent roles. In Goya’s late works, especially the Black Paintings, it becomes heavy and immersive, pressing in through walls and penetrating every colour. Manet’s use of black is unapologetic, confident, and frontal. He doesn’t soften or hide it in shadow. His blacks define the structure of the image, often becoming its visual anchor.

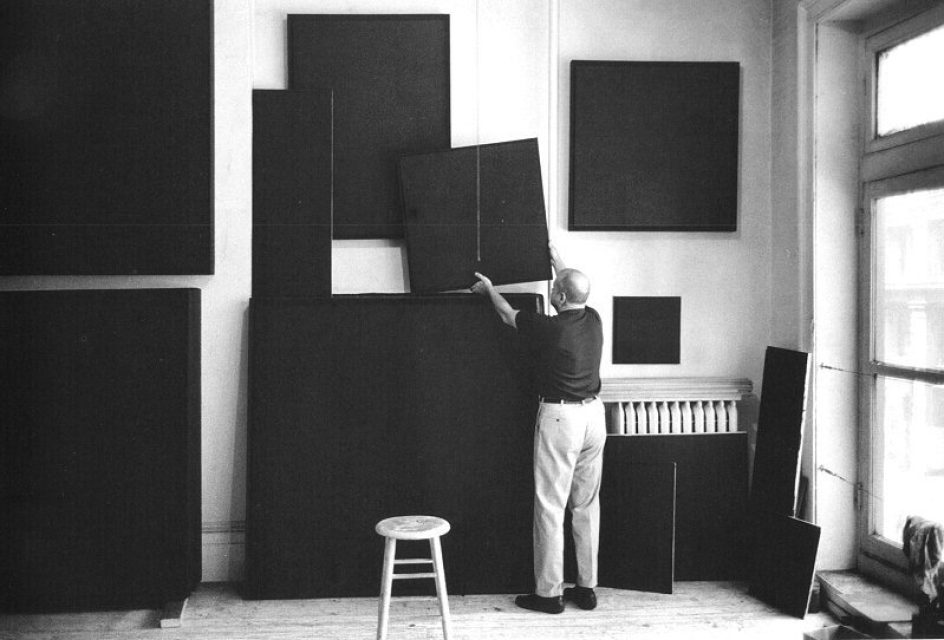

The twentieth century, with its strong belief in progress and ruptures, Black Square by Malevich marked what he called the zero of form, an end to illusionism, narrative, and external reference. Reinhardt painted almost-black grids and called them the last paintings anyone could make.

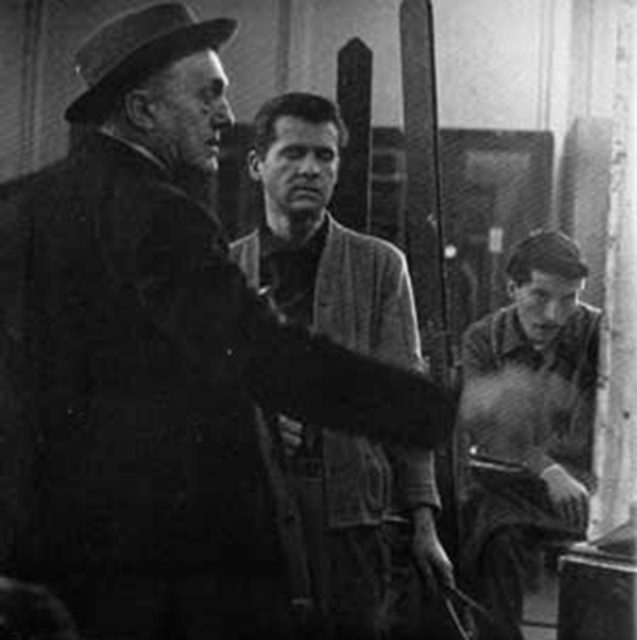

Max Beckmann, who was more concerned with the human condition than with purity or reduction, said in 1919: “My humility before God is over… My religion is defiance against God… In my paintings, I reproach God for everything he did wrong.” For him, a painting that refused suffering was unthinkable. So was one without black. Later, in his American exile, speaking little English, he was remembered pacing the studio, then urging his students with insistence toward using “More blek.”