I usually notice that a migraine aura starts to manifest because of a strange phenomenon. The exact point where I focus my eyes disappears. I can see all around it, but the middle of the focal point is gone. It is a peculiar inversion of normal seeing: the eye perceives everything except what it looks at.

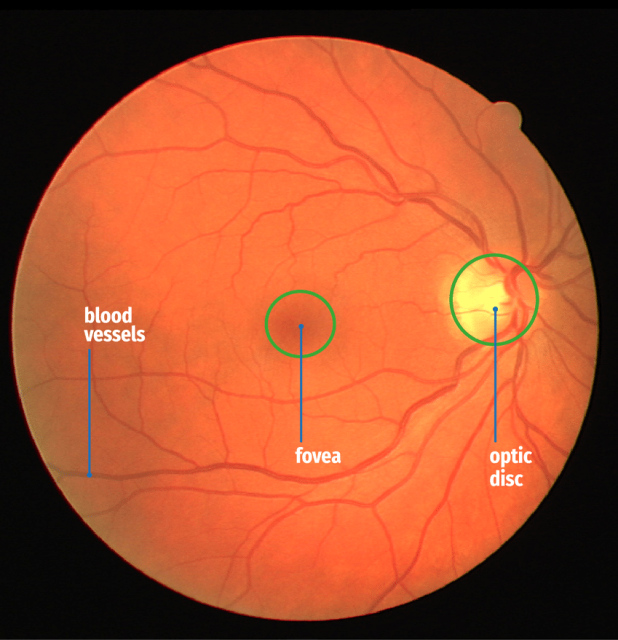

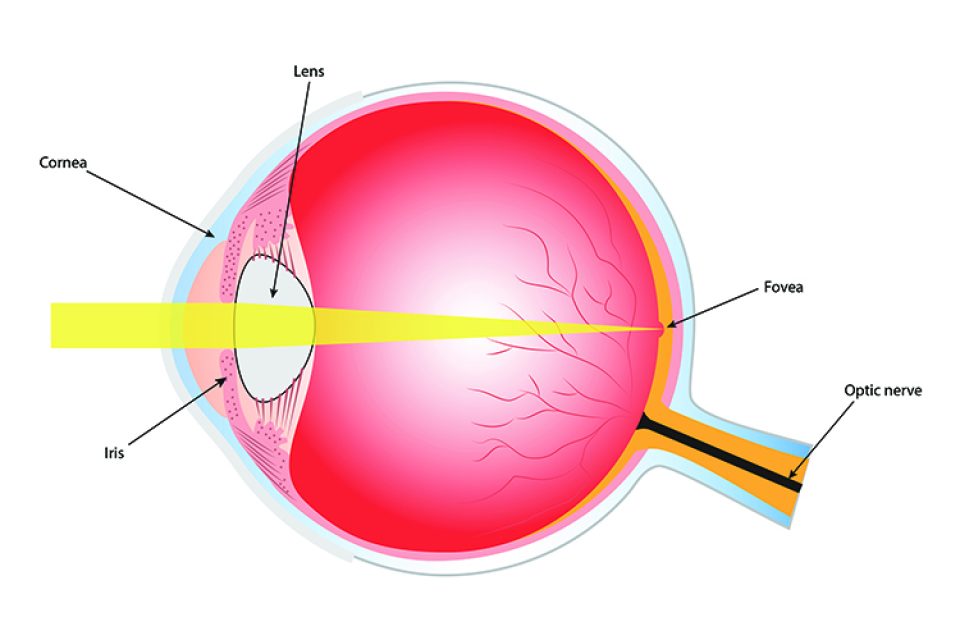

At normal times, it is within roughly two degrees of the visual field, about the size of a thumb held at arm’s length, that we see most clearly. The fovea, a small hollow about one and a half millimetres wide in the retina, is responsible for this sharp central vision. A disproportionately large share of the visual system is devoted to this minute area, even though it occupies only a tiny part of the retina. There are no blood vessels within it, keeping vision unobstructed.

What we perceive as a clear, wide, and steady image is mostly an illusion, assembled by the brain from countless brief glimpses and vague information. It feels stable but is largely a reconstruction, a moving point of clarity surrounded by blur.

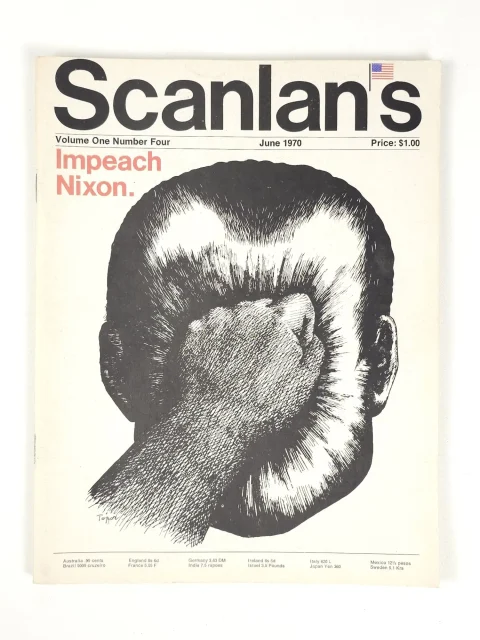

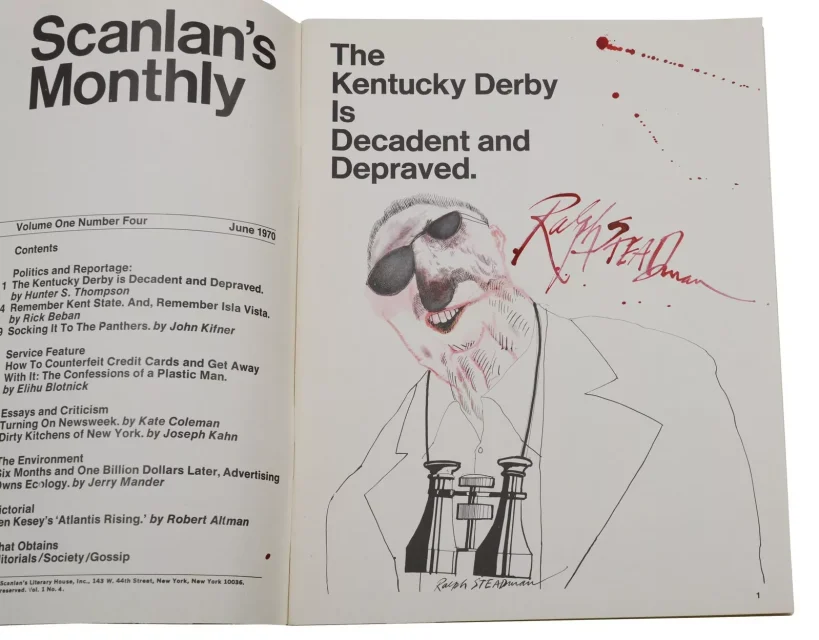

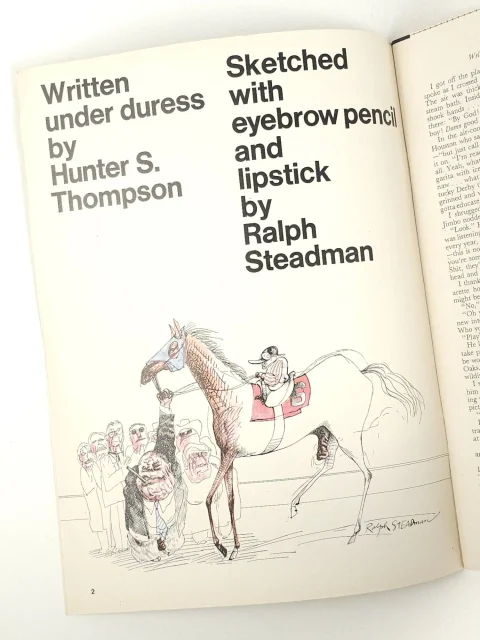

In the spring of 1970, Hunter S. Thompson travelled with the British caricaturist Ralph Steadman to Louisville to cover the Kentucky Derby for Scanlan’s Monthly. From the outset, the plan was not to report on the race itself. He proposed instead to write a first-person satire of Southern pageantry, a portrait of decadence and collapse seen from within rather than observed from above. Beneath the chaos of the Derby ran the tension of its time, a nation fractured by war, protest, and paranoia. “We came there to watch the real beasts perform,” he wrote. What followed was a deliberate experiment in radical subjectivity. Thompson placed himself at the centre, turning the event into a fevered reflection on excess, paranoia, and moral exhaustion.

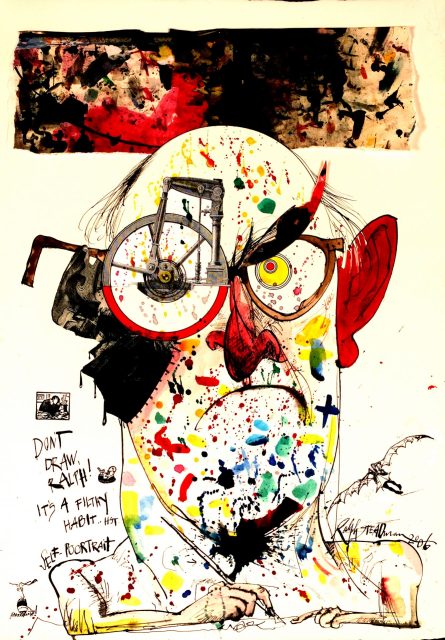

“I barely heard him. My eyes had finally opened enough for me to focus on the mirror across the room and I was stunned at the shock of recognition. For a confused instant I thought that Ralph had brought somebody with him — a model for that one special face we’d been looking for. There he was, by God — a puffy, drink-ravaged, disease-ridden caricature … like an awful cartoon version of an old snapshot in some once-proud mother’s family photo album. It was the face we’d been looking for — and it was, of course, my own. Horrible, horrible …”

Hunter S. Thompson’s article The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved is widely regarded as the first piece of Gonzo journalism. Traditional journalism treats the centre, the event and its facts, as the seat of truth, while the reporter remains at the periphery, seeking clarity through distance. In Gonzo, that clarity is inverted and exposed as an illusion. Thompson realises that “the race”, the official spectacle, reveals nothing essential about American life. The supposed centre is hollow, a distraction, while on its periphery the real meaning begins to appear.

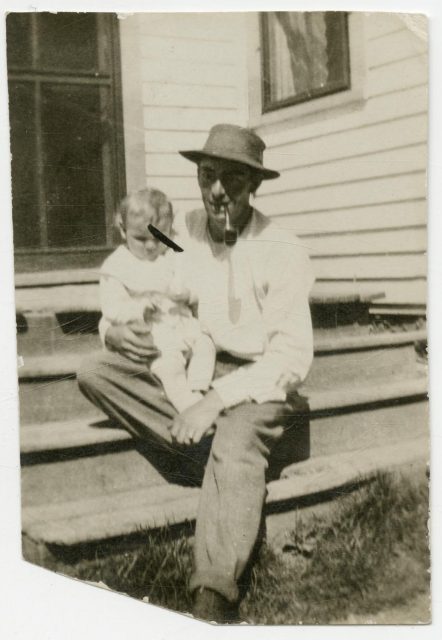

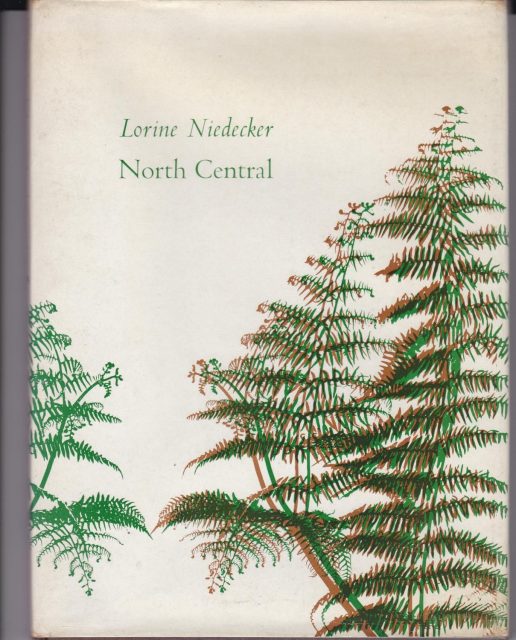

Lorine Niedecker spent most of her life on Black Hawk Island in rural Wisconsin, a narrow strip of low land bordered by backwaters and marshes where the Rock River sets the rhythm of life. It lies at the edge of land and water, between habitation and wilderness. Living far from the literary centres of her time, Niedecker wrote from economic precarity, working odd jobs and caring for her deaf mother.

Niedecker’s method enacts peripheral vision structurally. The poems present the self not as origin but as intersection, shaped by the forces that move around it. Observed fragments accumulate into a map of lived experience, charting a life by what forms it from the margins.

My Life by Water

My life

by water—

Hear

spring’s

first frog

or board

out on the cold

ground

giving

Muskrats

gnawing

doors

to wild green

arts and letters

Rabbits

raided

my lettuce

One boat

two—

pointed toward

my shore

thru birdstart

wingdrip

weed-drift

of the soft

and serious—

Water

![Philipp Fröhlich's painting La Périphérie [The Periphery] (351L), 2022, oil on canvas, 145 x 195 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Philipp_Frohlich_La_periferie_2022_145x195cm_351L.jpg)

![Philipp_Frohlich_La_periferie_2022_145x195cm_(351L) Philipp Fröhlich's painting La Périphérie [The Periphery] (351L), 2022, oil on canvas, 145 x 195 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Philipp_Frohlich_La_periferie_2022_145x195cm_351L-re42v1og18s2k3a04hdcff7ym2hheo1s257lhy9czk.jpg)