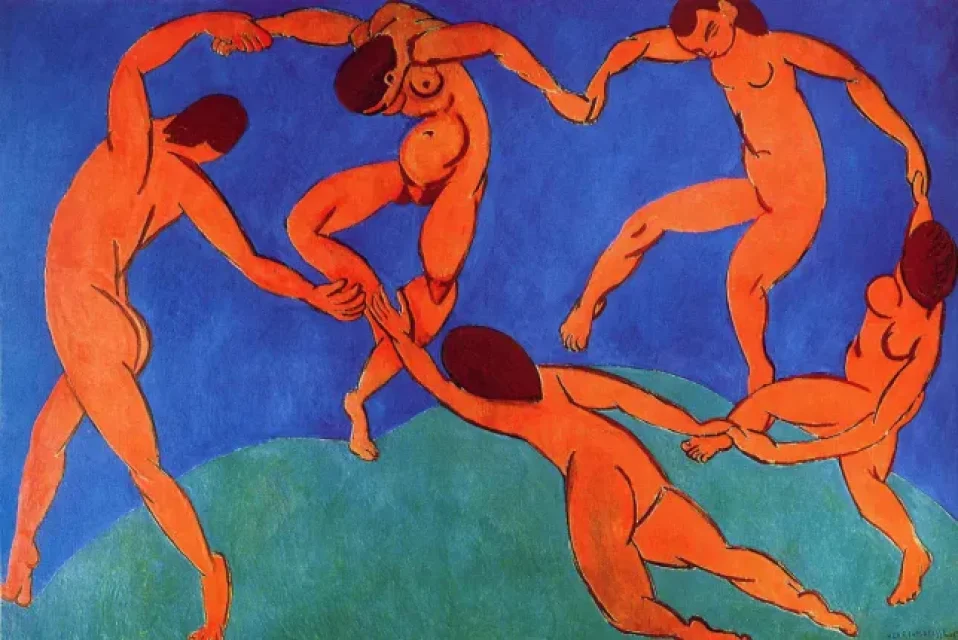

Rubens’ Dance of Mythological Figures and Villagers, tucked into a corner of the Prado, may be small by his scale, but it’s one of my favorites. A swirl of bodies, sweat, and joy—this is the group dance as ideal. Sensual and communal, fluid and timeless, it’s all about shared delight.

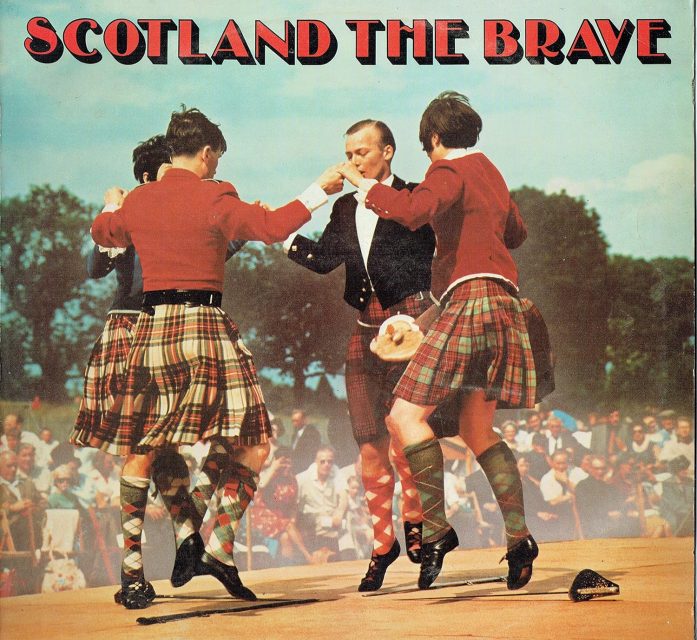

Years ago, I was invited to a Scottish party in Madrid and was stunned that everyone seemed to know—and willingly partake in—the group dances. There was something incredibly uniting in moving through a fixed, shared choreography.

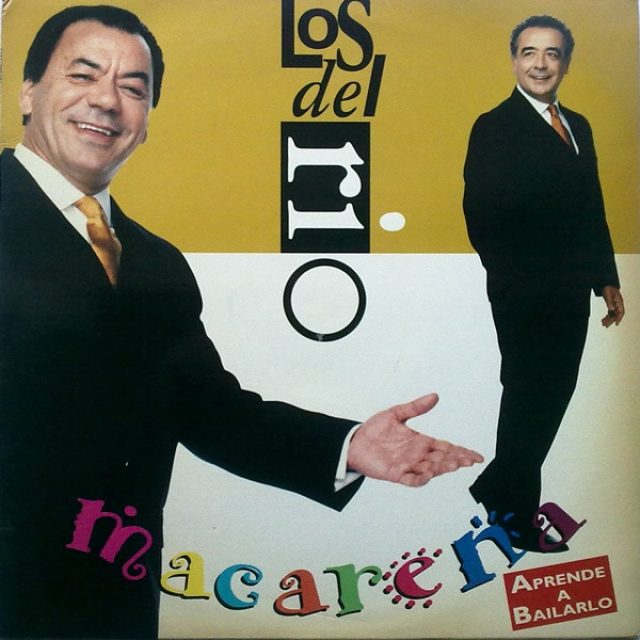

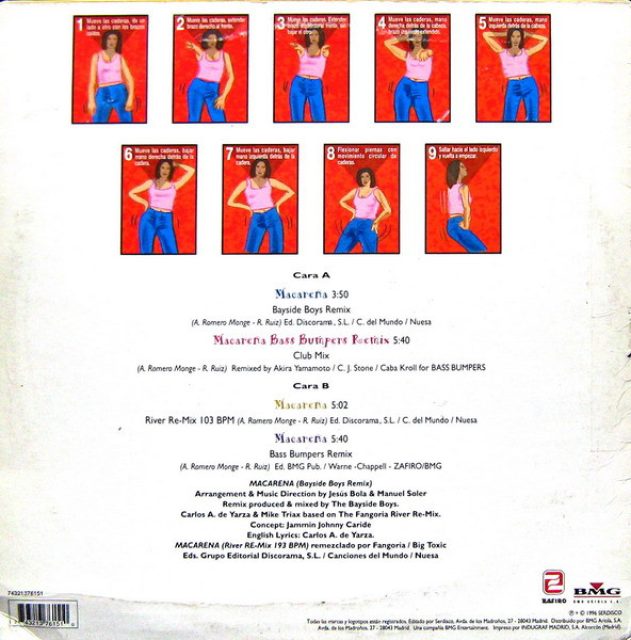

Then, a couple of weeks ago, I was invited to a Spanish wedding. It was a great party, but I couldn’t help noticing that the only collective dances were the Macarena and “Saturday Night.” As silly as they seem, there’s still an echo of ritual embedded in the kitsch. We gather, move, and mark time together—creating, however briefly, a shared group identity.

Being at the wedding made me think about how deeply the need for shared movement runs through human culture—whether preserved consciously or passed down in half-forgotten rituals.

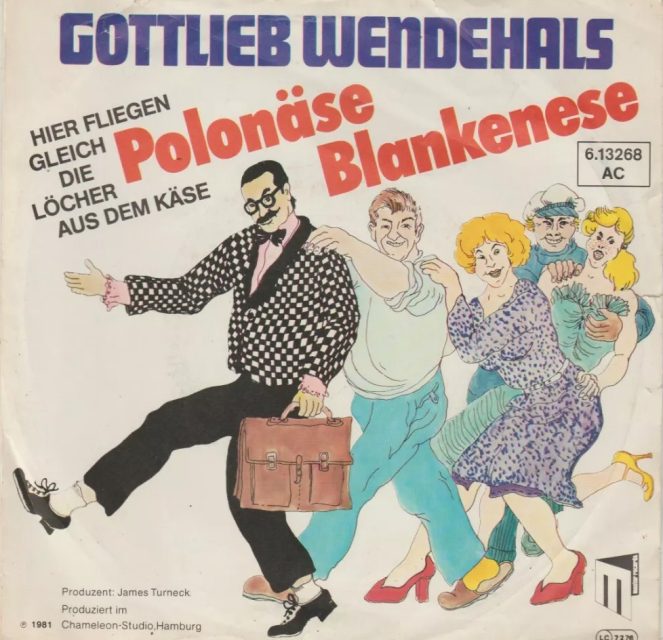

The winding procession of the Polonaise is especially apt for this. Participants snake around the room in an informal line, each placing their hands on the shoulders or waist of the person ahead. It might make us cringe, but its structure preserves remnants of processional ritual. And in its simplicity, it remains a masterpiece of inclusion.

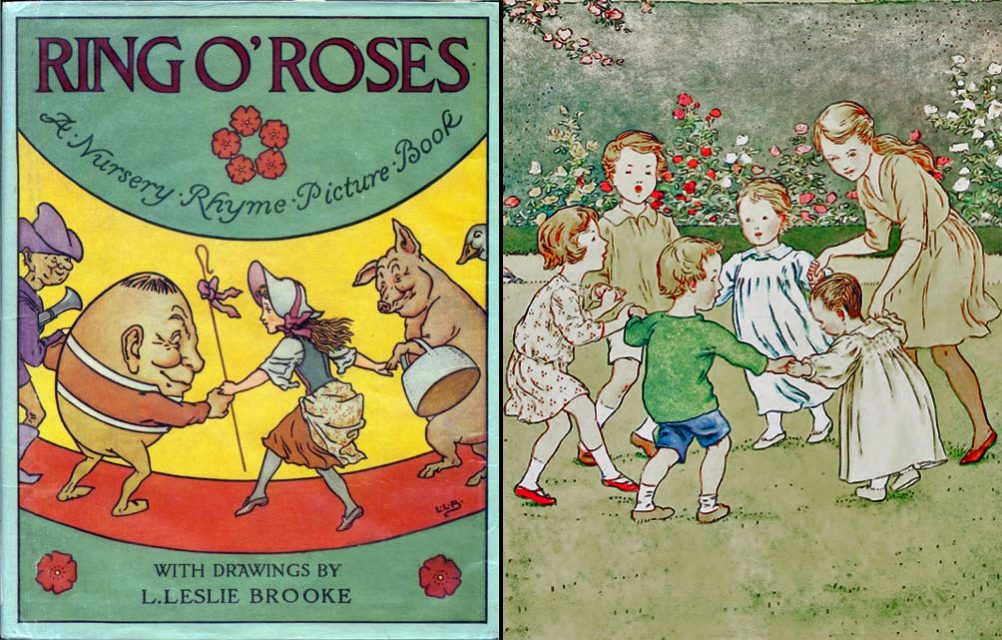

But the most basic—and at the same time the most meaningful—of all group dances is the circle dance. They range from children’s Ring a Ring o’ Roses to the famous circle dances of Native Americans and the Jewish Hora, to the ancient Choreia of Greece. There are even cave paintings showing human figures dancing in rings. Dancing in a circle is so inherently archaic that I doubt there is a culture that hasn’t adopted it in some form.

At the Carnival of Binche, the Gilles dance in slow, weighted circles, their movements heavy with ritual meaning but without a marked center. On Walpurgisnacht, witches dance around fires, and the center becomes a site of transformation and invocation. In Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the circle tightens to its extreme: a frenetic whirl that culminates in the selection and sacrifice of a single dancer.

The circle might be an empty space—an invocation of unity—or it can be a place of containment and transformation. To be at the center is to be marked. It is a site of honor, danger, or metamorphosis. In circle dances, the center can hold the fire, the chosen pair, the scapegoat, or the sacrificial victim. To be placed at the center is to be seen and set apart, to be celebrated or consumed.

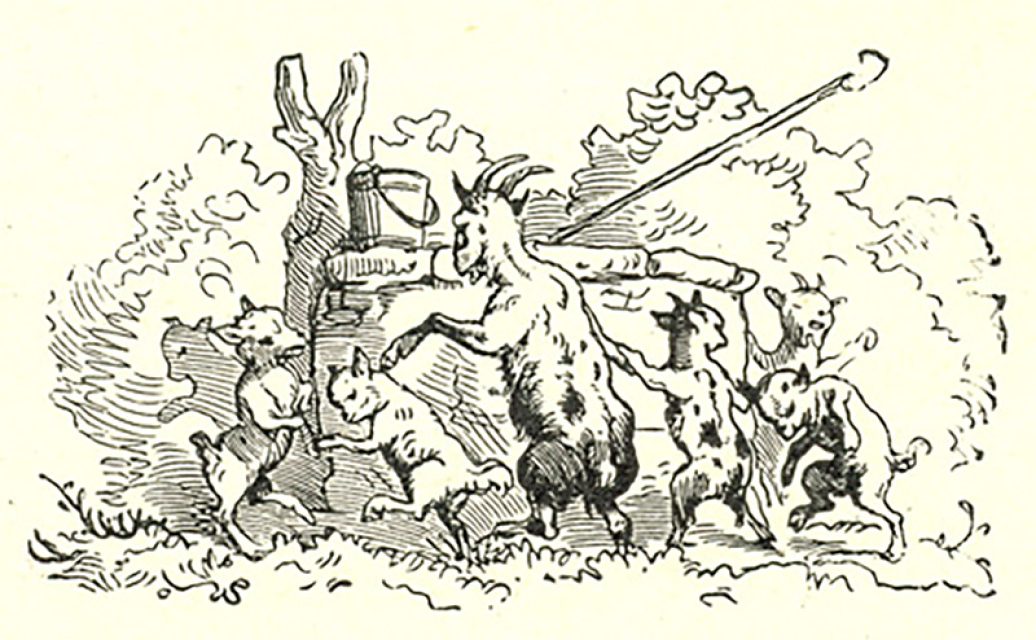

In the fairy tale The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids from the Brothers Grimm, it is the well that becomes the center. The wolf is tricked and drowned, his belly filled with stones, and cast down the vertical, dark axis in the middle. The goat kids, rebirthed out of the belly of the wolf, celebrate not just survival but the triumph of innocence over danger. It is the restoration of order—the brief, ecstatic moment when fear is overcome and turned into ritual motion.

![Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geisslein [The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids], (241L), 2019,oil on canvas, 275 x 195 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Philipp_Frohlich_Der_Wolf_und_die_sieben_jungen_Geisslein_2019-scaled.jpg)

![Philipp_Frohlich_Der_Wolf_und_die_sieben_jungen_Geisslein_2019 Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geisslein [The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids], (241L), 2019,oil on canvas, 275 x 195 cm](https://philippfrohlich.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Philipp_Frohlich_Der_Wolf_und_die_sieben_jungen_Geisslein_2019-scaled-r5ezylt5729z1zc4e99xu4yqxmmc0bzgm0uoddg5c0.jpg)