Following a harrowing night of emergency calls, Frank, played by Nicolas Cage in Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead, arrives at the apartment of Cy, a drug dealer. The space feels like a fantasy of relaxation. The walls are painted in dark red and deep green. There’s a painting of a volcano, quietly emitting real smoke. Light is low. Beds and sofas stand ready for exhausted minds. Cy calls it the oasis, a refuge from the world outside and what he calls Dayrise Enterprises, the stress-free factory. Fatigued, emotionally drained, and riddled with guilt, Frank accepts a handful of pills to calm his nerves. As the music shifts from the weighty rhythm of Burning Spear’s I and I Survive to the more upbeat yet serene Rivers of Babylon by Boney M, and his gaze fixes on the soft glow of an aquarium, Frank begins to drift.

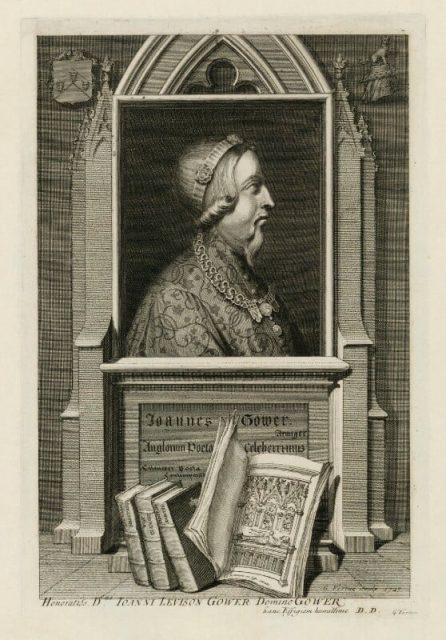

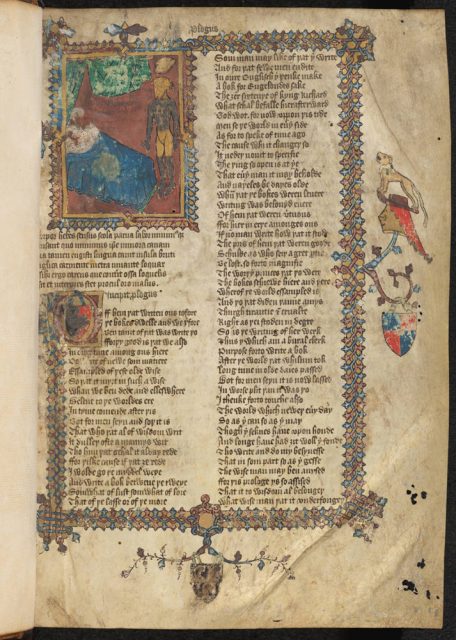

My introduction to the house of the god of sleep, Hypnos, came through the lyrics of Current 93’s album Sleep Has His House. The song The God of Sleep Has Made His House is a gentle, modern rendering of a passage from John Gower’s Confessio Amantis. What follows is a pairing of both texts, with the lyrics presented in italics.

The god of Slep hath mad his hous

The god of sleep has made his house

Which of entaille is merveilous.

Of marvellous design

Under an hell ther is a Cave,

Under a hill there is a cave

Which of the Sonne mai noght have,

Which of the sun may nothing have

So that noman mai knowe ariht

So that no man may know aright

The point betwen the dai and nyht.

The point between the day and the night

Ther is no fyr, ther is no sparke

Ther is no cok to crowe day,

There is no cock to crow the day

Ne beste non which noise may.

Neither beast which might noise make

Ther is growende upon the ground

There is growing on the ground

Popi, which berth the sed of slep,

Poppy which bears the seed of sleep

A stille water for the nones

A still water all the time

Rennende upon the smale stones,

Is running over the small stones

Which hihte of Lethes the rivere

Ther is, which yifth gret appetit

And it gives great desire

To slepe.

To sleep

And thus full of delit

And thus full of delight

Slep hath his hous.

Sleep has his house

It’s a beautiful and fascinating idea, to think of sleep not as an action but as a place. An architecture shaped by the absence of stimulation. No sun, no time, no sound. Just the trickling of water, the presence of poppies, and a dark cave where sensory input fades. Oblivion not as emptiness, but as interior.

In late spring we went to Cantabria to visit friends, enjoy the stunning landscape, and explore as many caves as possible. Conservation of the Neolithic paintings is a concern, so access is limited to only a few visitors each day. It’s a tremendous experience. You enter through a slit in the rock. Light is dim, or you need a flashlight to see at all. After just a few steps, the temperature settles into a humid cool that remains the same year-round. It feels archaic, almost like stepping out of time, and strangely familiar. To imagine how humans entered these spaces thousands of years ago, carrying only a flickering, bone-marrow-fueled light, to leave their images behind in the darkness is astonishing. It’s like an attempt to mark oblivion.

In his autobiography, Johnny Cash writes about entering Nickajack Cave with the desire to die in its depths. It was the low point of his life, with addictions to various substances and his private life a mess. The experience becomes a turning point. In the dark silence, he begins to feel his surroundings again: the stone, the air, the faint drift of a breeze. Slowly, he makes his way back out.

Maybe sleep is a kind of rehearsal for death. Although there is a stark contrast between the desire for oblivion that we all might feel when going to sleep each night, and the reality of what we are offered in an involuntary way. It’s the echoes of our mind refusing to be silent. Robert Frost captures this tension in his poem After Apple-Picking:

My long two-pointed ladder’s sticking through a tree

Toward heaven still,

And there’s a barrel that I didn’t fill

Beside it, and there may be two or three

Apples I didn’t pick upon some bough.

But I am done with apple-picking now.

Essence of winter sleep is on the night,

The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.

I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight

I got from looking through a pane of glass

I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough

And held against the world of hoary grass.

It melted, and I let it fall and break.

But I was well

Upon my way to sleep before it fell,

And I could tell

What form my dreaming was about to take.

Magnified apples appear and disappear,

Stem end and blossom end,

And every fleck of russet showing clear.

My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.

And I keep hearing from the cellar bin

The rumbling sound

Of load on load of apples coming in.

For I have had too much

Of apple-picking: I am overtired

Of the great harvest I myself desired.

There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch,

Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall.

For all

That struck the earth,

No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble,

Went surely to the cider-apple heap

As of no worth.

One can see what will trouble

This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is.

Were he not gone,

The woodchuck could say whether it’s like his

Long sleep, as I describe its coming on,

Or just some human sleep.