In a small painting, the entire world is there before you. Every edge, every mark is visible at once. There is no guesswork, and the results are immediate.

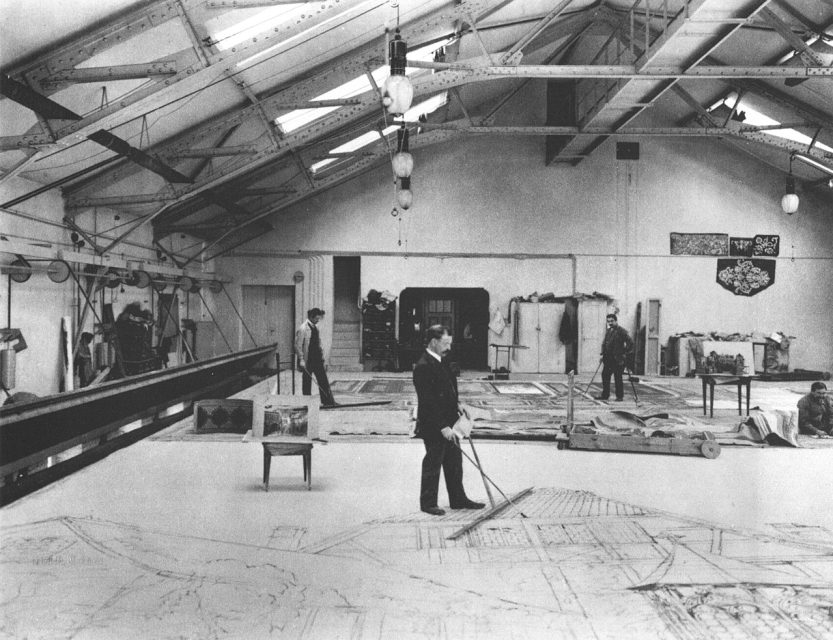

A small painting is contained. A large canvas is something else entirely. Standing in front of it, at arm’s length, you can only grasp a part. You have to step back to see the whole, and sometimes that means painting from a ladder or crouching on the floor. The whole process becomes more physical.

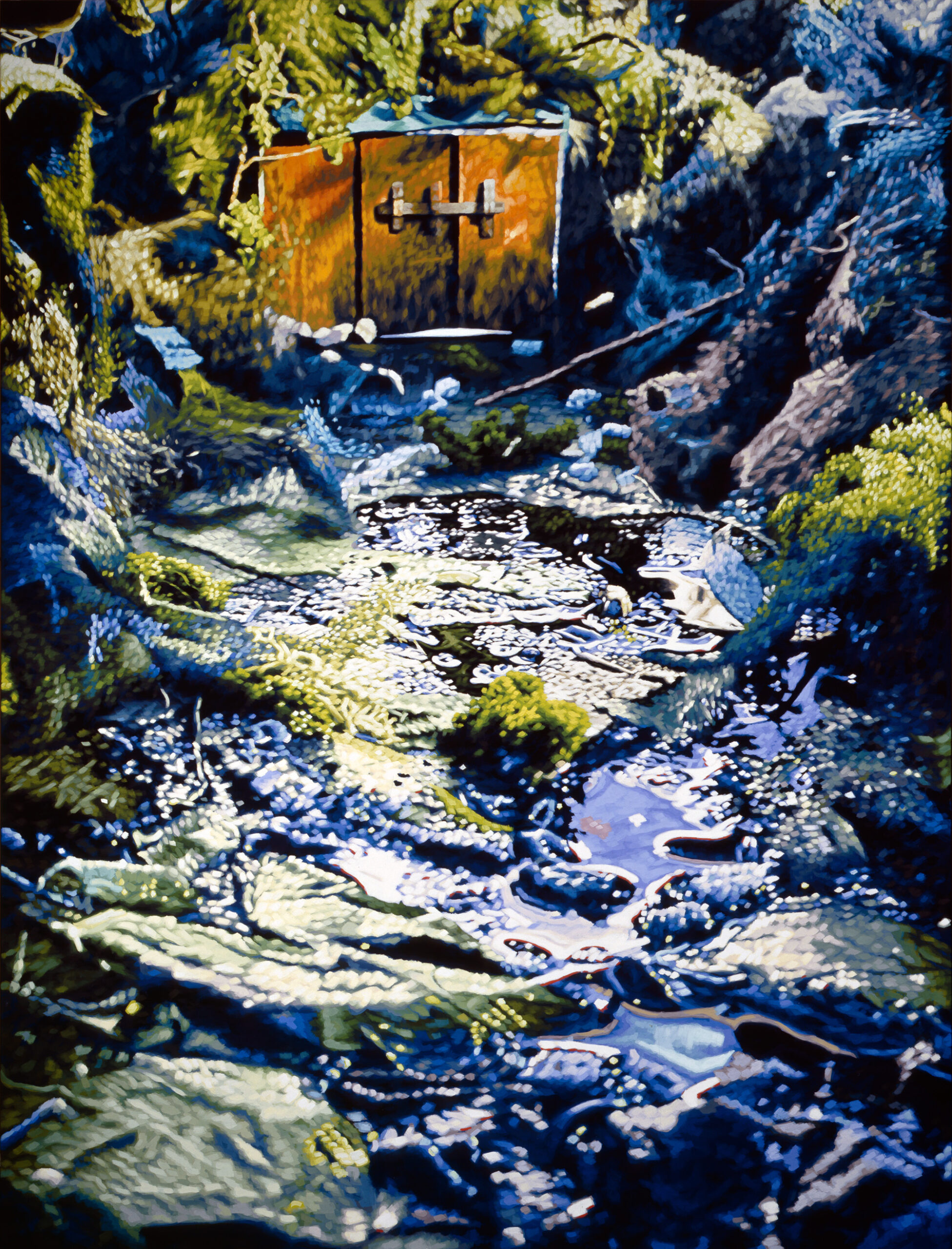

Beginning a large painting always gives me great pleasure. I can use big brushes and plenty of paint, and enjoy the broad, gestural movements. But soon reality sets in: the image is still only a flat sketch of what I had in mind. This continues until I reach one particular moment, when the surface seems to open up and fold around me and I feel as if I am painting from within. The painting stops being a surface and becomes its own dimension, architectural and enveloping. In that moment, it is as if I am standing inside my own stage set, my own theatre.

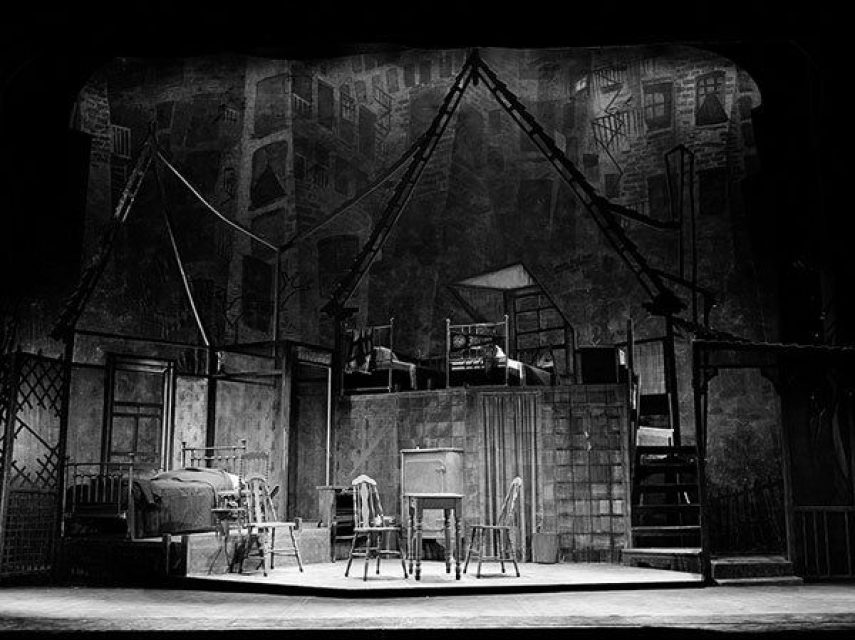

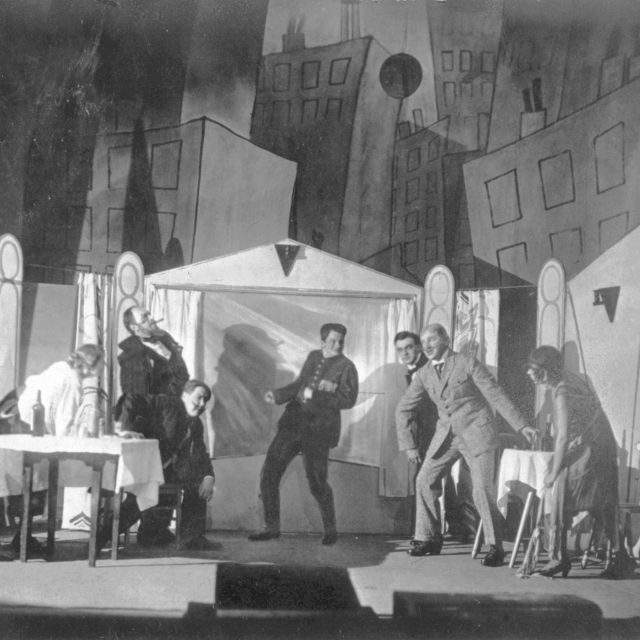

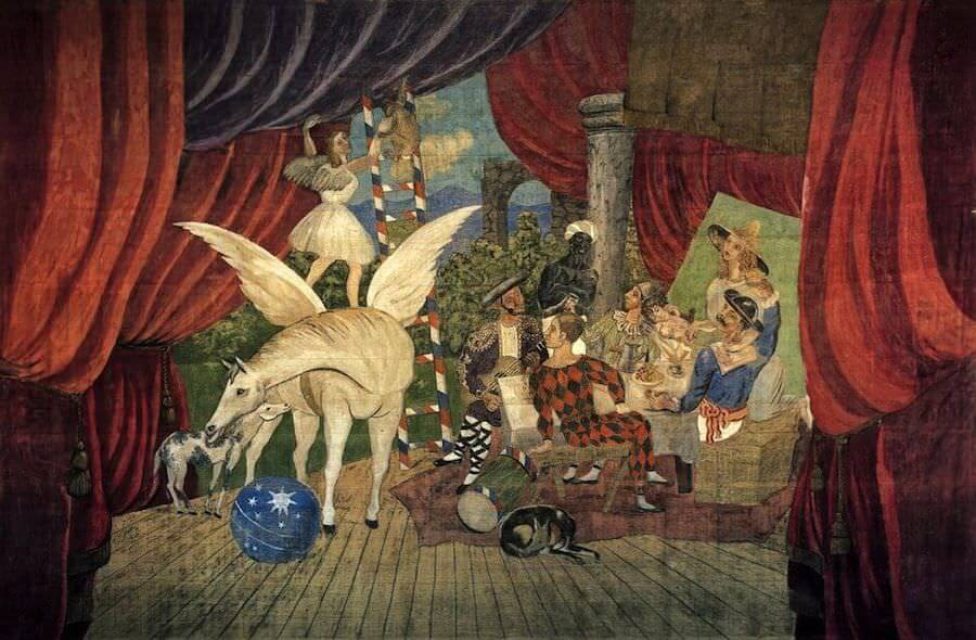

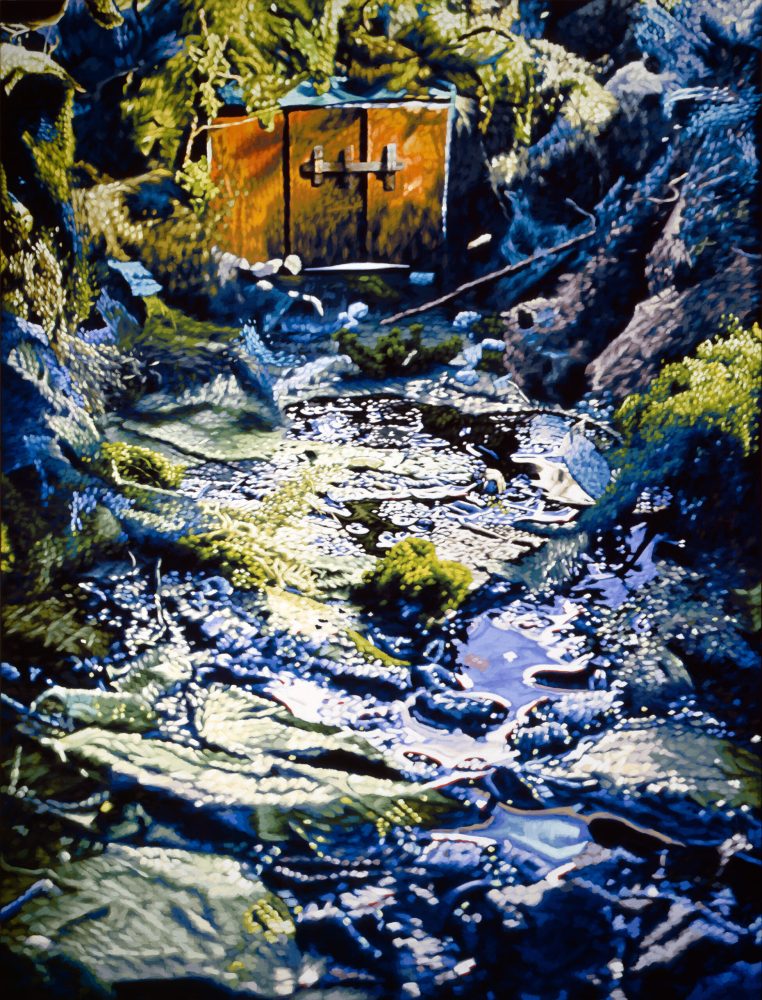

I’ve always had a soft spot for painted scenic backdrops in the theatre, those vast painted canvases that both describe a world and make no secret of their artifice, though they are rare today.

At first glance, a scenic backdrop might seem naïve, a hopeless attempt at creating an illusion that everyone will see through immediately. But a well-made, well-used painted backdrop can be much more.

A painted backdrop can fix the time and place of a scene by evoking a historical period, a season, a time of day, or by establishing a location.

It might be architectural, suggesting buildings and spaces, or atmospheric, shaping mood through light, colour, texture, or weather.

It can give context, frame the action, or expand the stage space through perspective. Sometimes it anchors the scale of the actors, sometimes it distorts and unsettles.

It may blend into the theatre’s architecture or stand apart as something entirely alien.

It can hint at stories, hold the memory of past performances, or reference other artworks.

Yet it is not possible to truly interact with a painted backdrop. You cannot use it as a realistic point of entry, nor can you interact with what is represented. It works on a completely different level from the actors.

And perhaps that is the point: nothing states more clearly that what you see is not reality but a stage. It’s a convention and a partnership. It immediately defines the person on the stage as an actor, and only through the actor’s presence does the backdrop make sense.

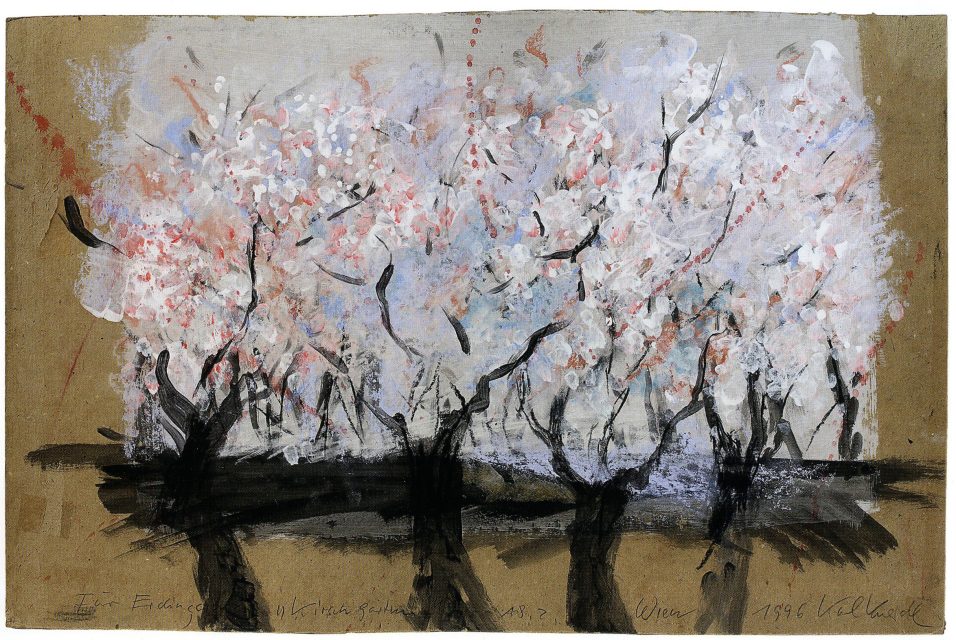

Of course, painted theatre backdrops are only distantly related to ordinary paintings, but I often think of them while working on a large-scale canvas. This particular canvas, above, was bought by my friend Antonio Fernandez Villalba. In a photograph from the exhibition he stands in front of it, leaning to one side, arms folded, with a conspiratorial smile. We met after my first group show, when he phoned me out of the blue and invited himself to my studio. At first, I could barely understand his thick Murcian accent, but we became great friends immediately. Fifteen years ago this month, while I was on vacation, my gallerist Soledad Lorenzo called to tell me he had died in a car crash. He was one of those rare people whose absence never stops being felt.