I very nearly burned down my studio while preparing the mockup for this painting in 2009. I wanted the light in the center to look undefined, so I piled up a chaotic mix of materials: cotton, paper, plastic foil, and a generous amount of steel wool. The light source was a chain of Christmas lights, wound into the heap. What I didn’t know was that steel wool can catch fire from even a small electrical charge, like a battery. The threads crept between the bulbs and wires, and suddenly there were sparks and small fires. Luckily, I had a fire extinguisher within reach. Unluckily, it was a powder extinguisher, and green dust settled into the smallest corners of the studio. I kept finding it for years in drawers, on shelves, in the folds of fabric. Its residue kept surfacing.

Spectators sometimes assume that the light is a sunset. Others read it as an explosion. For me, it will always be the moment my studio nearly caught fire. The ambiguity is what interests me most. It’s a seductive light in the background. What matters most to me is the skeletal hedge in the foreground. It’s a barrier, a frontier. You can see that something is happening beyond it, but you can’t reach it. The surface holds you back. For now, you remain an onlooker. A witness. Maybe a voyeur.

Thresholds are a recurring concern of mine. I often think of the surface of the painting as a kind of plane, a boundary between the world around it and the world it contains.

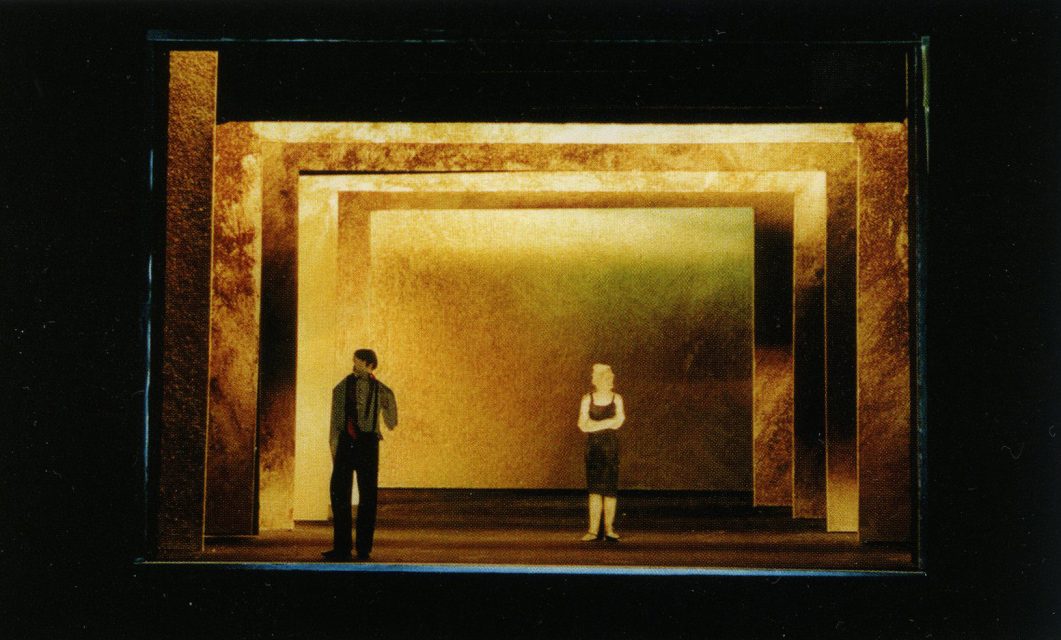

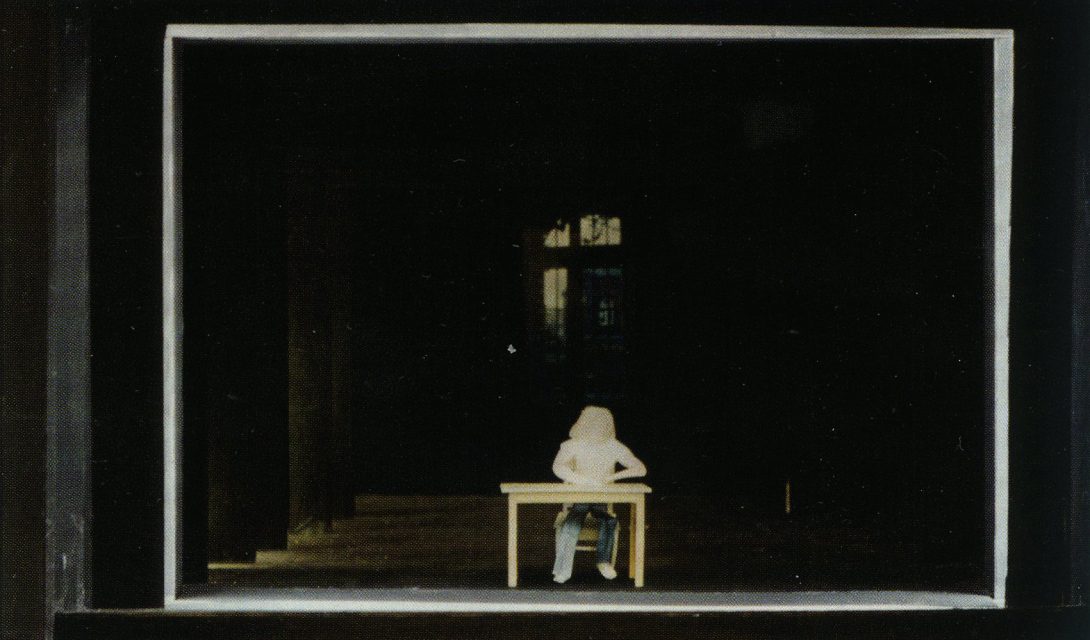

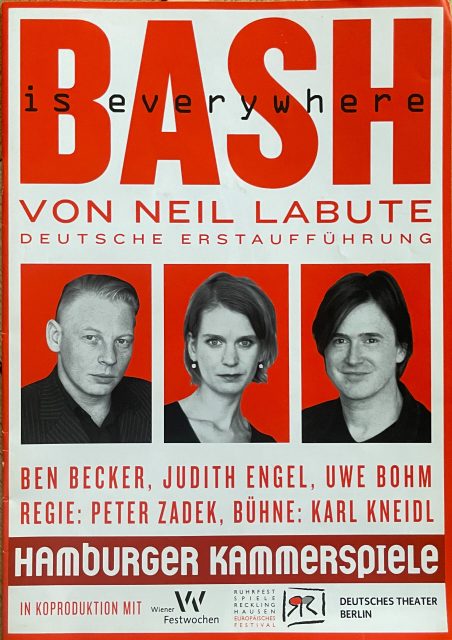

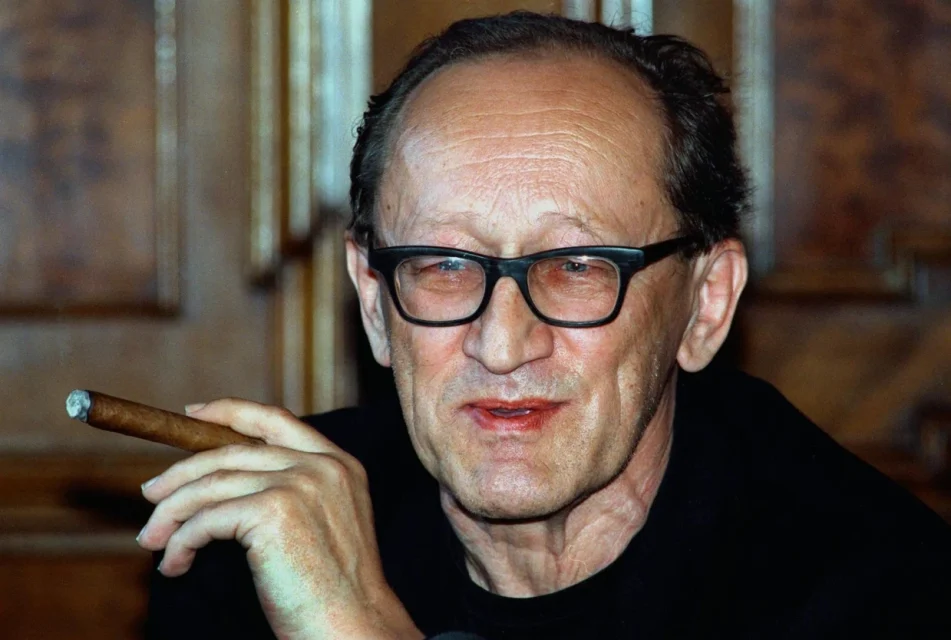

In 2001, I was assisting my professor, Karl Kneidl, on the scenography for Neil LaBute’s play Bash at the Hamburger Kammerspiele. Peter Zadek directed the production. The play consists of two monologues and a dialogue in between, each one a confession of murder. The stage was stripped to a few elements: a single chair, a painted fragment that might hint at the scene. Between the sections, a light frame around the theater portal would illuminate, briefly blinding the audience. When the light faded, the next monologue began. The inspiration for this light frame came from Heiner Müller’s poem DRAMA:

The dead wait on the opposing slope

Sometimes they hold a hand into the light

As if alive. Till they withdraw completely

Into their familiar darkness which blinds us.

Working on this play was a turning point for me. The theater portal became a threshold, not just between audience and stage, but between this world and another. Not imagined, but real in a different way. That invisible seam between two realities became an obsession. In recent years, I’ve begun adding white frames with an inward slope for the same reason, to mark that crossing.

After leaving the theater, my attention turned to painting and to how viewers relate to its surface.

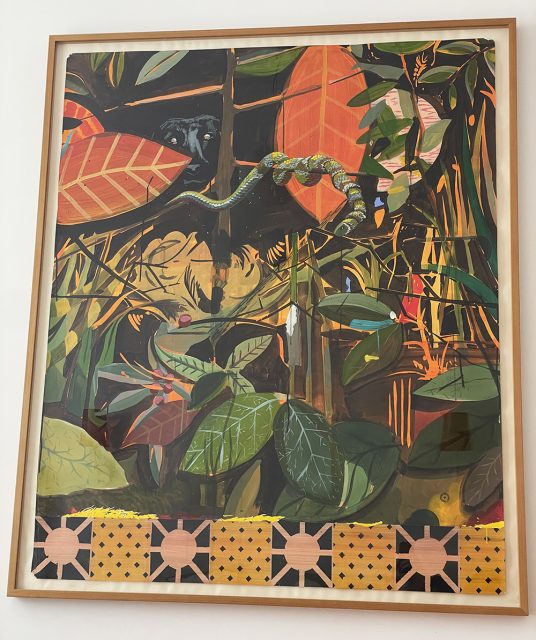

On the wall opposite my bed hangs a large painting by Miki Leal that I bought years ago. I see it every night. It shows a jungle, mostly large leaves and branches, with a patterned section at the bottom. The forms are flat, with no real sense of depth. Everything sits flush against the paper. Even the snake, curled in the upper middle, seems pressed against the skin of the image. Only the black gorilla, peeking out from between the leaves, breaks that plane. It looks directly at you, mirroring the viewer. It’s no longer clear who is observing whom.

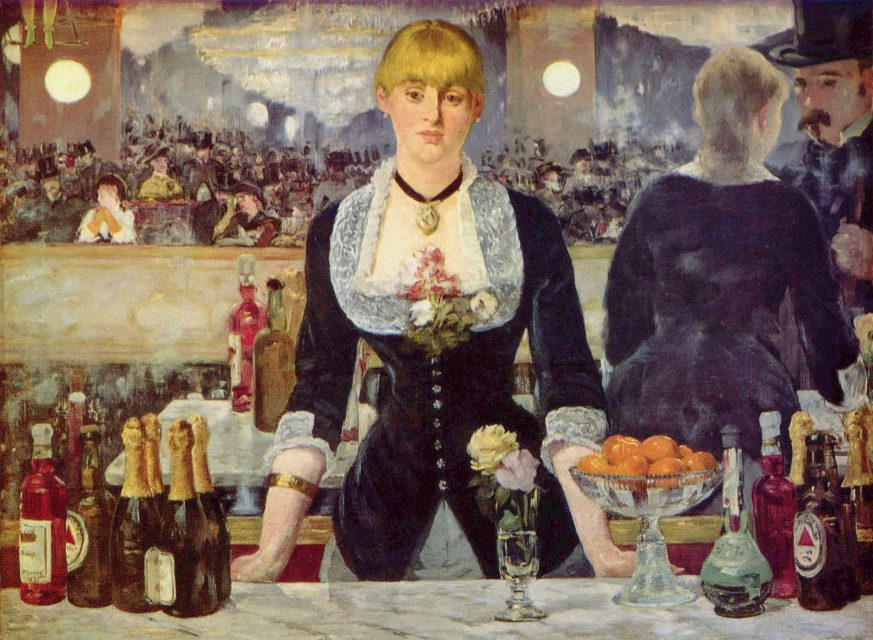

Jeff Wall’s Picture for Women has always struck me in this regard. The woman stands on the left, the photographer on the right, and the camera sits exactly in the middle, pointing straight at the viewer. The image is based on Manet’s Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, but Wall takes its confrontational gaze a step further. What seems like a stable triangle of subject, artist, and audience begins to unravel. The photograph doesn’t just depict a scene, it reproduces the mechanics of its own making. The invisible mirror that must have been used becomes a threshold in itself, dividing roles that are usually assumed to be fixed. If you look closely, a vertical seam runs straight through the camera’s lens, the join between two photographs. Wall once said of this detail: “The join between the two pictures brings your eye up to the surface again and creates a dialectic that I always enjoyed and learned from painting… a dialectic between depth and flatness.”

This flatness is also what makes Hiroshi Sugimoto’s theater series so relevant. Each photograph is a long exposure taken over the full duration of a film. The screen appears as a white rectangle in an otherwise empty movie theater. You see two realities at once: the physical architecture of the space, and the presence of the film, which is no longer decipherable. The movie is reduced to a rectangular field of light, not an image but a surface. It becomes the threshold itself.

My favorite painted threshold is the chapel of San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid, painted by Goya. The paintings revolve around a story from the life of Saint Anthony of Padua: his father is accused of murder, so the saint resurrects the victim to clear the accusation and name the true killer.

In Goya’s vision, the viewer becomes the body in the tomb. You see angels and cherubim lifting the draperies of your deathbed. Just above the visitor, the architectural circle becomes the edge of your grave, a threshold. In the cupola, enclosed by a low fence, stand the witnesses: people right out of Goya’s Madrid, with the saint, the victim, and the murderer, surrounded by trees, hills, and open sky.

It’s an astonishing effect, likely the only time you’ll ever be able to look out from your own grave. The height of the dome adds to this, making you feel powerless in your own fate. You are ready to rise, but only at the saint’s will.

The greatness of Goya’s proposition lies in the violence with which he forces you into a role almost no one wants to inhabit. You’re no longer just a witness. You’re what they’ve gathered to see.