In 1992, I spent half a year attending school in Leicester, England. Wanting to explore the area, I decided to skip class once a week and visit places that interested me. One morning, I set out to see Bosworth Battlefield—the site of the final major conflict in the Wars of the Roses, fought in 1485. It was there that Henry Tudor defeated Richard III. It’s also where Shakespeare has Richard cry, “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”—before being killed in battle, alongside some 1,200 soldiers.

It wasn’t easy to get there. I took several tiny buses and eventually reached Bosworth Market. Rain was pouring down. A kind woman in a shop took pity on me, locked up her store, handed me an umbrella, and drove me the last few miles to the battlefield.

When I arrived, it was just a patch of grass.

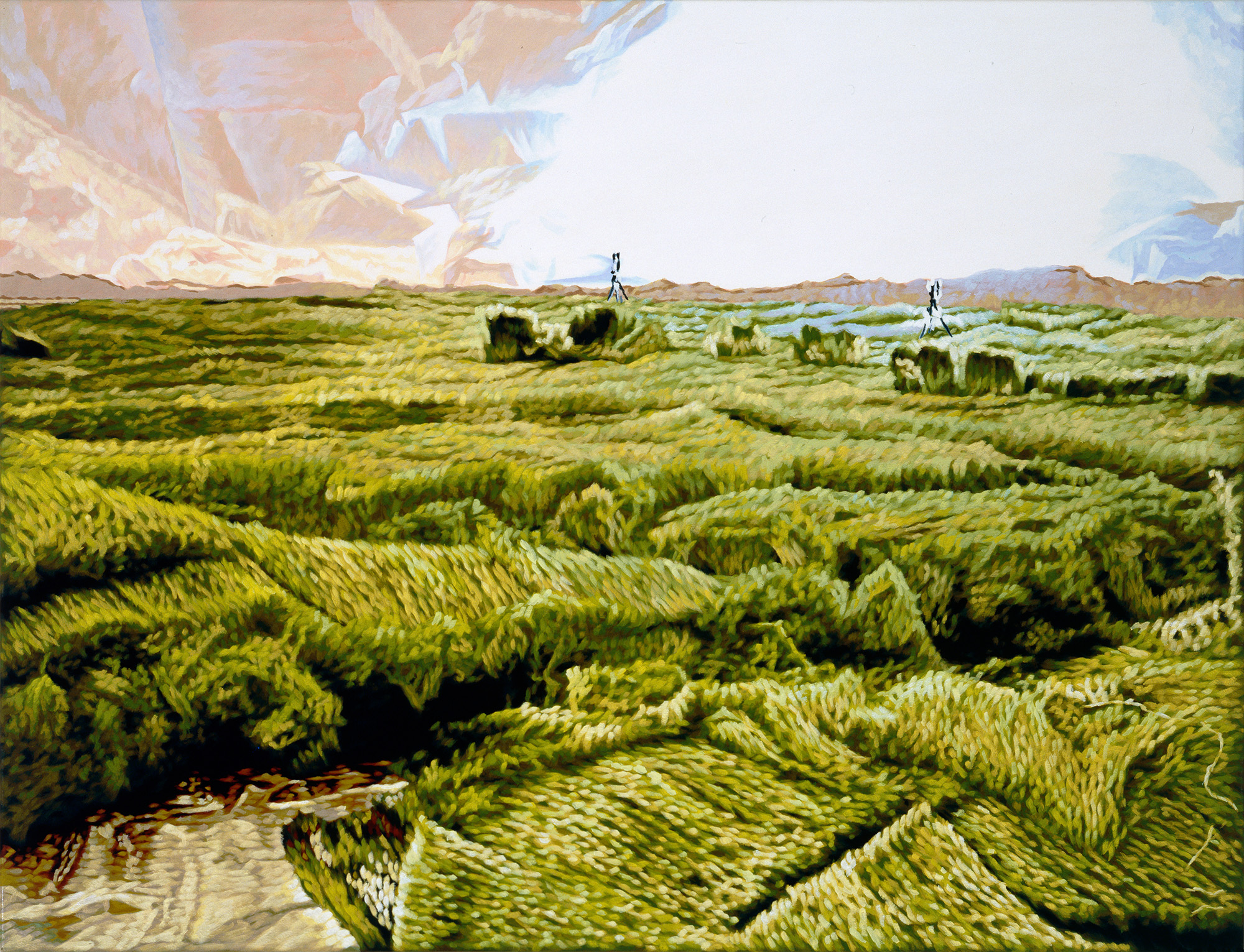

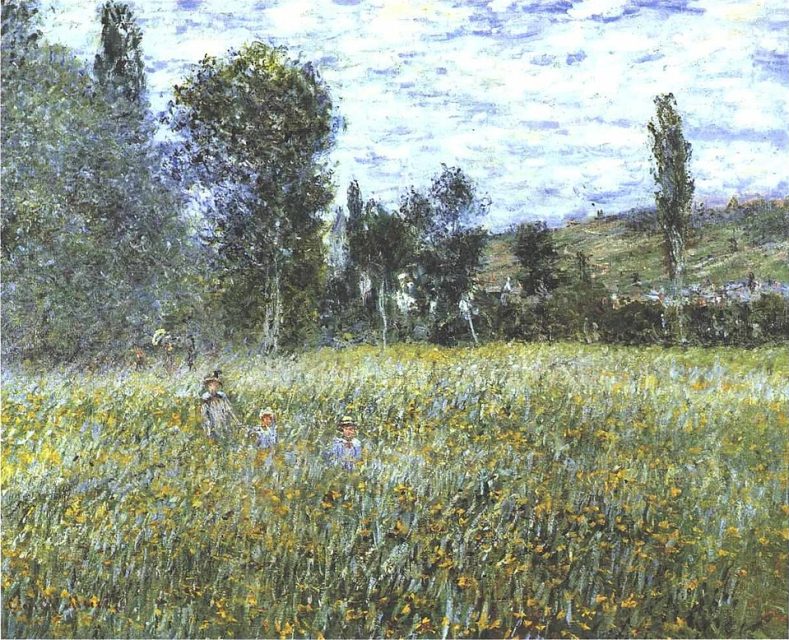

I remember walking over the wet, muddy field, trying to summon the image of a medieval battle and imagine the fighting soldiers, charging knights, all the noise and turmoil. But I could only see the plain green grass. Years later, in 2010, archaeologists discovered that the actual site of the battle lay about two kilometers away. I hadn’t even stood on the “real” ground where it happened. But even there, at the actual site, there is nothing to see. Just grass.

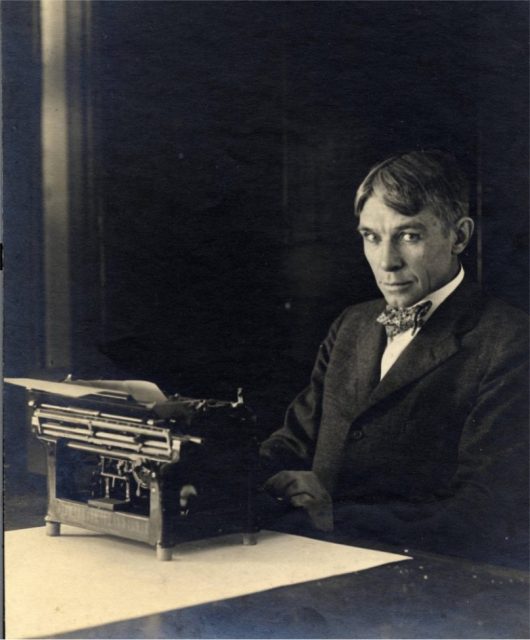

Some years later, a friend’s father, who was a professor of English literature, introduced me to Carl Sandburg’s poem Grass, from his 1918 collection Cornhuskers:

Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me work—

I am the grass; I cover all.

And pile them high at Gettysburg,

And pile them high at Ypres and Verdun.

Shovel them under and let me work.

Two years, ten years, and passengers ask the conductor:

What place is this?

Where are we now?

I am the grass.

Let me work.

The German phrase “Gras drüber wachsen lassen” (literally, “let grass grow over it”) means to let time pass until something is forgotten or buried. It’s about moving on—quietly, sometimes perhaps conveniently.

Grass is like a carpet. It covers everything underneath.

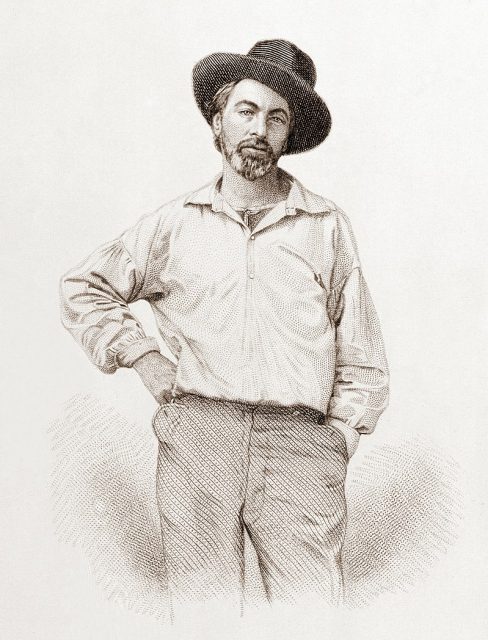

In his collection Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman calls it “…the beautiful uncut hair of graves.”

He continues:

Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them,

It may be you are from old people, or from offspring taken soon out of their mothers’ laps;

And here you are the mothers’ laps.

This is not a sentimental image, but a deeply physical one, radical in its tenderness. Grass becomes the medium through which the dead return to the living—not in glory, but in green. It’s not decorative. It’s not cultivated. It grows on its own terms, curling softly over the dead. It refuses the verticality of monuments, offering instead the horizontal logic of the leveling. Where stone insists on permanence, grass accepts decay. It grows over borders, ignores inscriptions, and eventually reclaims the ground from all claims to ownership. Grass is not interested in legacy. It doesn’t commemorate—it absorbs.

Richard III’s own burial tells a strange and poignant story. After his death at Bosworth, his body was taken to Leicester and buried without ceremony in the choir of the Greyfriars friary—a modest resting place for a king. But that grave, too, was eventually lost. When Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, the friary was destroyed, and whatever marker had stood above Richard’s remains disappeared. For over 500 years, no one knew exactly where he lay.

In 2012, archaeologists found him under a municipal car park in Leicester. Paved over, unmarked, almost forgotten. A monarch reduced to myth, then found beneath painted lines and tarmac. No tomb, no grass—just layers of earth and asphalt.

In 2015, Richard III was reburied in Leicester Cathedral, beneath carved stone and solemn ceremony.

The monarch finally got his monument.